The film is conscious of the class dimensions to all this. Shizuku lives in a cramped apartment where she has to share a room with her older sister. Her lovesick best friend lives in a mansion by comparison, and her paramour Seiji also commutes from a fancier neighbourhood. Shizuku's mother is studying for an MA and her sister is saving money so she can move into her own apartment – both are focused on getting on in the world and find Shizuku's diversions from her schoolwork baffling. Her father is a librarian, and content with his job and position in life, which allows him to be more supportive of his daughter's artistic development. But it's clear that Shizuku doesn't have some of the advantages of her school friends, which stack the odds against her succeeding as a writer.

Showing posts with label Anime. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Anime. Show all posts

25.4.20

Whisper of the Heart (If You Listen Closely)

This is one of Miyazaki's finest works. He wrote the script, but the director is Yoshifumi Kondō – a rising star at Studio Ghibli who tragically died before he could make more films. It's a mostly realistic story about a bright high school girl who has to navigate a love triangle, the pressures of studying and her own budding abilities as a creative writer. The love triangle is almost a Shakespearian comedy, with lots of characters liking the wrong person or not realising who they really like. It culminates in a powerful scene in which Shizuku rejects a suitor, after which this plot strand is largely abandoned. Instead the film turns to explore the tension between artistic ambition and the daily demands of life, school and work.

Shizuku's relationship with her mysterious classmate (who hangs out with his antiquarian grandfather and wants to learn how to make violins in Italy) turns into an intellectual partnership as much as it is a young romance. Exposure to this new household filled with intriguing objects and where people have the opportunity to develop their creative talents is a spur for Shizuku to finish writing her own first story, to the point where she has to abandon studying for her exams. The effort is not cost-free – Shizuku's family become concerned about her behaviour and her grades. But in a heartwarming scene Shizuku's father intervenes on her behalf, giving her the support she needs to complete her personal project.

The film is conscious of the class dimensions to all this. Shizuku lives in a cramped apartment where she has to share a room with her older sister. Her lovesick best friend lives in a mansion by comparison, and her paramour Seiji also commutes from a fancier neighbourhood. Shizuku's mother is studying for an MA and her sister is saving money so she can move into her own apartment – both are focused on getting on in the world and find Shizuku's diversions from her schoolwork baffling. Her father is a librarian, and content with his job and position in life, which allows him to be more supportive of his daughter's artistic development. But it's clear that Shizuku doesn't have some of the advantages of her school friends, which stack the odds against her succeeding as a writer.

While the film is a melodrama, it's refreshingly grounded about these obstacles and burdens. The romance between Shizuku and Seiji is founded on an acknowledgement of their particular creative interests, and the understanding that they are to be nurtured despite the anguish of separation that might involve. It is a partnership in which each supports the other to fulfill themselves. The film's final scene, in which Shizuku and Seiji race up a hill to catch the sunrise, becomes a metaphor for their relationship, with Shizuku getting off Seiji's bike to push together towards their shared goal.

The film is conscious of the class dimensions to all this. Shizuku lives in a cramped apartment where she has to share a room with her older sister. Her lovesick best friend lives in a mansion by comparison, and her paramour Seiji also commutes from a fancier neighbourhood. Shizuku's mother is studying for an MA and her sister is saving money so she can move into her own apartment – both are focused on getting on in the world and find Shizuku's diversions from her schoolwork baffling. Her father is a librarian, and content with his job and position in life, which allows him to be more supportive of his daughter's artistic development. But it's clear that Shizuku doesn't have some of the advantages of her school friends, which stack the odds against her succeeding as a writer.

19.2.20

Only Yesterday (Memories Come Tumbling Down)

A carefully-wrought, subtle drama from Studio Ghibli's other great maestro Isao Takahata. It reminded me a bit of George Eliot's The Mill on the Floss, in that the depiction of the protagonist's childhood puts her adult character in perspective, although the connections are elliptical and sometimes mysterious. Nevertheless a picture emerges of a spirited young girl who is overlooked, insulted and on one occasion straight-up abused by her family – not out of spite or ill-will, but because her parents are tired and confused and don't have the emotional resources to support their youngest child. The result is an outwardly successful young woman with a job in Tokyo who feels like a ghost.

The solution to Taeko's alienation is a holiday to the countryside, where she joins the villagers in their back-breaking agricultural work. The family relationships she discovers there go some way towards mending the traumas buried in her past. The contrast between town and country is a well-worn trope, but the most impressive thing about the film is that it always endeavours to strike a balance between idealism and realism. An example is the organic farmer lecturing on the importance of respecting nature, but also admitting to using weedkiller because there just isn’t enough agricultural labour in modern times to pull the weeds out by hand.

Another example comes at the end when the possibility is raised of Taeko giving up life in the city and finding romance in the countryside. She treats this as a ridiculous suggestion and describes it as something out of a film. The irony, of course, is that this is a film, and in the final moments she does turn back. But this surrender is presented as a fantasy – it's part of the credits sequence where the music swells and the ghosts of the past appear to guide Taeko to happiness. It's where the film abandons verisimilitude and turns overtly film-like, and the balance tips into unadulterated romanticism. It feels like something that happens after the story has ended and Taeko goes back to Tokyo. I suspect Takahata wanted to give his audience a reward for persevering with the difficult work of a woman coming to terms with her past. But that reward is offered grudgingly, presented as a flight of fancy – almost an afterthought. As Taeko says, it's something that happens in films but is impossible in real life.

The solution to Taeko's alienation is a holiday to the countryside, where she joins the villagers in their back-breaking agricultural work. The family relationships she discovers there go some way towards mending the traumas buried in her past. The contrast between town and country is a well-worn trope, but the most impressive thing about the film is that it always endeavours to strike a balance between idealism and realism. An example is the organic farmer lecturing on the importance of respecting nature, but also admitting to using weedkiller because there just isn’t enough agricultural labour in modern times to pull the weeds out by hand.

Another example comes at the end when the possibility is raised of Taeko giving up life in the city and finding romance in the countryside. She treats this as a ridiculous suggestion and describes it as something out of a film. The irony, of course, is that this is a film, and in the final moments she does turn back. But this surrender is presented as a fantasy – it's part of the credits sequence where the music swells and the ghosts of the past appear to guide Taeko to happiness. It's where the film abandons verisimilitude and turns overtly film-like, and the balance tips into unadulterated romanticism. It feels like something that happens after the story has ended and Taeko goes back to Tokyo. I suspect Takahata wanted to give his audience a reward for persevering with the difficult work of a woman coming to terms with her past. But that reward is offered grudgingly, presented as a flight of fancy – almost an afterthought. As Taeko says, it's something that happens in films but is impossible in real life.

6.1.19

Blame!

Am quite partial to the far future cyberpunk visions of Tsutomu Nihei. This Netflix film adaptation of his manga has him on board as writer and creative consultant, and is a good introduction to his particular grim style. Imagine if the Matrix sequels dispensed with the philosophical gobbledigook and focused on mood, action and the encroaching threat of the elimination of the species.

Much of the appeal here isn't plot or even character, which is rudimentary, but the gorgeous look and feel. And the studio Polygon Pictures have really gone to town on creating the sort of effects that throw you into proceedings – camera shifts and judders that reflect the shockwaves of the fireworks on screen. It's very enjoyable nonsense, but proof if any were needed of Nihei's unique imaginative gifts.

28.10.18

Maquia: When the Promised Flower Blooms

An overlong high-fantasy anime released this year. It concerns a race of immortal weavers who isolate themselves from the world and record its history through the reams of tapestry they produce. The main character Maquia is warned off forming attachments by the clan's chief, who says such entanglements end in unhappiness. To love is to be alone.

The story is set up to refute this thesis. Maquia's home is attacked and she finds herself stranded far away from her country. Moreover, she finds a newborn child whose mother has been murdered, and decides to adopt and care for him. The immortal is brought down to earth, and has to deal with the real-world pressures of motherhood. Although the anime wanders off into a steampunky Laputa-esque fantasy narrative about clashing kingdoms, that stuff ultimately provides a backdrop for Maquia's relationship with the growing Ariel, who she looks over as he matures, falls in love and has children of his own.

Parenting is therefore the central theme of the story. The decision to have children is a way of ending your detachment from the world. You have skin in the game in a way you don't when you dispassionately look over events from an ivory tower, as the weavers (literally) do. It's significant that the director Mari Okada is one of the few female creators making internationally-fêted anime films. It's a valuable perspective to have in what is mostly a male-dominated industry.

The anime strains very hard to build to an emotionally powerful ending, slipping into melodrama if not bathos in the effort. I found this a bit cloying and wearying, and note that the understated approach of masters like Miyazaki and Takahata is often more effective. Okada also doesn't effectively integrate the personal story of Maquia and Ariel with the wider tale of the kingdom they live in. Instead there are awkward leaps between one and the other, making the whole thing feel longer than its 115 minutes. It's not perfect, in other words. But then again, there's also nothing quite like it.

The story is set up to refute this thesis. Maquia's home is attacked and she finds herself stranded far away from her country. Moreover, she finds a newborn child whose mother has been murdered, and decides to adopt and care for him. The immortal is brought down to earth, and has to deal with the real-world pressures of motherhood. Although the anime wanders off into a steampunky Laputa-esque fantasy narrative about clashing kingdoms, that stuff ultimately provides a backdrop for Maquia's relationship with the growing Ariel, who she looks over as he matures, falls in love and has children of his own.

Parenting is therefore the central theme of the story. The decision to have children is a way of ending your detachment from the world. You have skin in the game in a way you don't when you dispassionately look over events from an ivory tower, as the weavers (literally) do. It's significant that the director Mari Okada is one of the few female creators making internationally-fêted anime films. It's a valuable perspective to have in what is mostly a male-dominated industry.

The anime strains very hard to build to an emotionally powerful ending, slipping into melodrama if not bathos in the effort. I found this a bit cloying and wearying, and note that the understated approach of masters like Miyazaki and Takahata is often more effective. Okada also doesn't effectively integrate the personal story of Maquia and Ariel with the wider tale of the kingdom they live in. Instead there are awkward leaps between one and the other, making the whole thing feel longer than its 115 minutes. It's not perfect, in other words. But then again, there's also nothing quite like it.

28.9.18

Cowboy Bebop

Anime scholar Susan Napier suggests that the final two-part episode manages to reconcile ironic detachment and a conventional portrayal of the male hero:

But the series asks you to watch it in a different way – suspending the need for narrative continuity across episodes, or the urge to develop lasting themes that linger beyond the great song that plays over the closing credits. Bebob is about surfaces, and its attitude is playful rather than sincere. It's a procession of skits referencing effects and affects from other works, scrambling them together into a collage which asks you to admire its audacity, but doesn't really engage your feelings.

If anything the final few episodes draw attention to the unreal, no-stakes mode in which the anime operates. Faye Valentine finds her childhood home and leaves the adventuring life aboard the Bebop, but then realises she has nothing to go back to – she ends up rejoining the gang, finding her real family in the process. She arrives in time to warn Spike away from going back to his past, as she did. It's better to forget. But for Spike these adventures they've had together are just a dream he's been sleepwalking through. He needs to confront his origins in order to work out if he's really alive. Spike's tragedy is that he chooses Julia over Faye, a real past over an unreal present.

That reality has stakes – Julia dies, Jet gets injured, the Bebop is shot down, Spike himself is left for dead. Perhaps it's better to stay dreaming. Interestingly the standalone film (released after the series but set before the finale) warns against the seductive power of dreams. In the world of Cowboy Bebob you have to choose between meaningless death-defying spectacle or the real world of mortality and lost love.

"Perhaps Cowboy Bebop's greatest contribution to the construction of masculinity is the way it convinces its audience that traditional heroism and chivalry can exist within a postmodern framework."That's a lot of weight placed on Spike's story, which sticks rather closely to the doomed noir antihero narrative, including a damselled and fridged femme fatale to add a bit of motivation to an otherwise supremely louche character. A cynic would say that this is just another mode the anime plays with – a genre it adopts for a 23-minute spin of the turntable before moving on to horror, farce, heist, sci-fi, action, comedy etc etc etc. How far can we take these personalities seriously, given they shift with the tropes they are required to embody?

But the series asks you to watch it in a different way – suspending the need for narrative continuity across episodes, or the urge to develop lasting themes that linger beyond the great song that plays over the closing credits. Bebob is about surfaces, and its attitude is playful rather than sincere. It's a procession of skits referencing effects and affects from other works, scrambling them together into a collage which asks you to admire its audacity, but doesn't really engage your feelings.

If anything the final few episodes draw attention to the unreal, no-stakes mode in which the anime operates. Faye Valentine finds her childhood home and leaves the adventuring life aboard the Bebop, but then realises she has nothing to go back to – she ends up rejoining the gang, finding her real family in the process. She arrives in time to warn Spike away from going back to his past, as she did. It's better to forget. But for Spike these adventures they've had together are just a dream he's been sleepwalking through. He needs to confront his origins in order to work out if he's really alive. Spike's tragedy is that he chooses Julia over Faye, a real past over an unreal present.

That reality has stakes – Julia dies, Jet gets injured, the Bebop is shot down, Spike himself is left for dead. Perhaps it's better to stay dreaming. Interestingly the standalone film (released after the series but set before the finale) warns against the seductive power of dreams. In the world of Cowboy Bebob you have to choose between meaningless death-defying spectacle or the real world of mortality and lost love.

19.8.18

A Silent Voice (The Shape of Voice)

A two-hour teen drama anime that's on Netflix at the moment. My wife wanted to watch something romantic in the spirit of Your Name (which we both love). Indeed, Makoto Shinkai thoroughly recommended A Silent Voice when it came out, but actually it is both a darker and more flawed piece of work. First the darkness – the anime begins with a suicide attempt by a teenage boy, before we flashback to his primary school years where he horrifically bullies a new deaf student. The initial flood of sympathy for the character curdles as we see him shout at her, throw dirt in her face and rip out her hearing aids. The incidental details lend credibility to the depiction: the teacher is young, bored and ineffective; the are no father-figures anywhere to be seen. It's a useful corrective to to the idea that Japanese children are somehow always well-behaved, dutiful and hard-working.

The anime is about how as a teenager Shōya starts to atone for the mistakes he made as a boy, and learns how to build real friendships. Some of this is handled expertly. The pressure of social opprobrium is what leads to his feelings of worthlessness – suicide for several characters is seen as a way to remove a burden on others. If they can't get anything right, they might as well cease to exist.

The anime missteps when it dilutes its sense of realism by indulging in unnecessary theatrics. It starts out as a drama and increasingly slips into melodrama. At its most fanciful the anime contrives a serendipitous midnight meeting which is arranged almost telepathically. When the manipulation of an audience's feelings is this discernable, it loses its force. And there are several moments towards the end which stumble as a result. That's a shame, because with a few tweaks A Silent Voice could have hit just as hard as Shinkai's superhit.

The anime is about how as a teenager Shōya starts to atone for the mistakes he made as a boy, and learns how to build real friendships. Some of this is handled expertly. The pressure of social opprobrium is what leads to his feelings of worthlessness – suicide for several characters is seen as a way to remove a burden on others. If they can't get anything right, they might as well cease to exist.

The anime missteps when it dilutes its sense of realism by indulging in unnecessary theatrics. It starts out as a drama and increasingly slips into melodrama. At its most fanciful the anime contrives a serendipitous midnight meeting which is arranged almost telepathically. When the manipulation of an audience's feelings is this discernable, it loses its force. And there are several moments towards the end which stumble as a result. That's a shame, because with a few tweaks A Silent Voice could have hit just as hard as Shinkai's superhit.

28.2.18

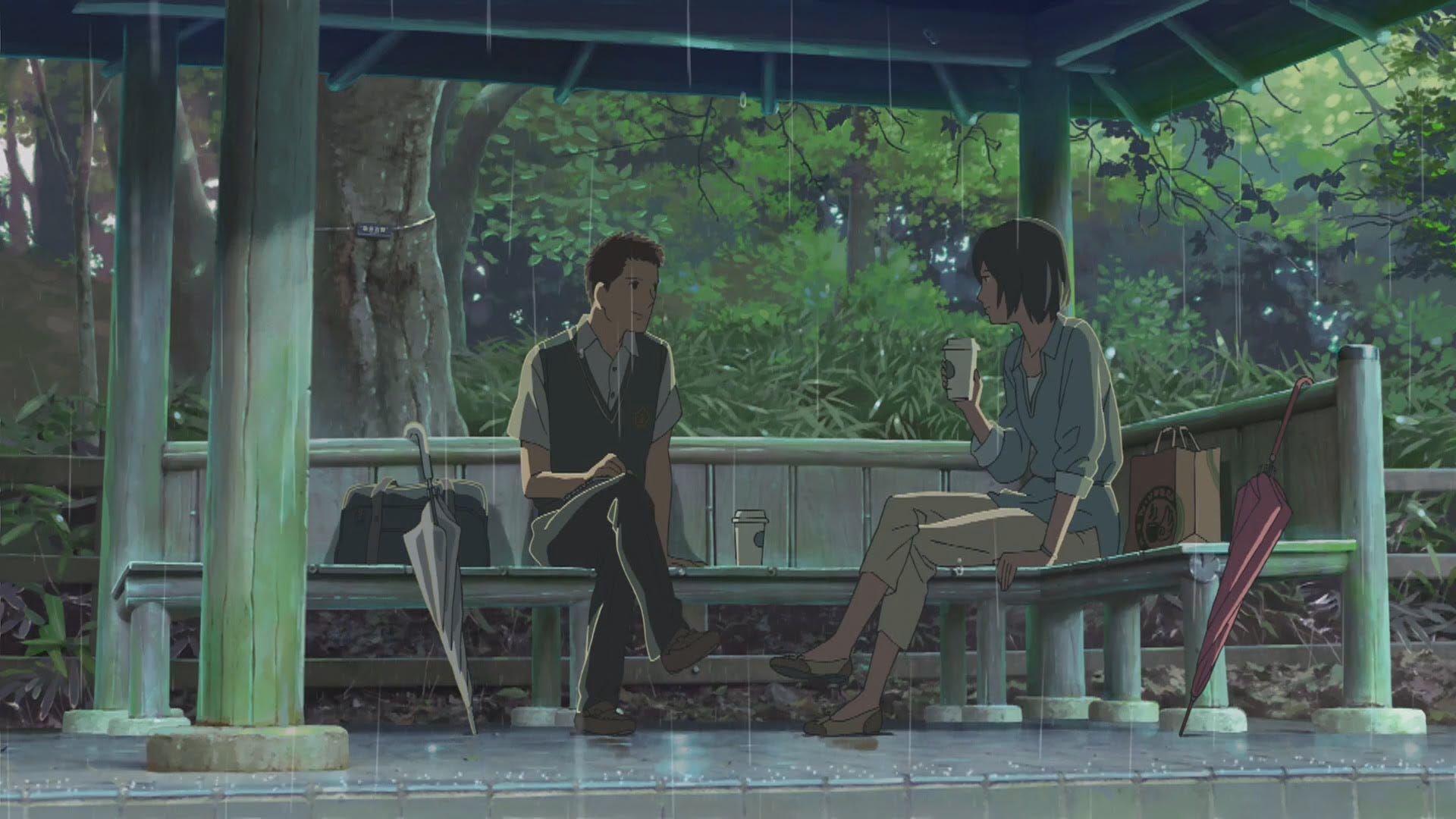

The Garden of Words

The feature Makoto Shikai made before the phenomenally successful Your Name has come on Netflix. It’s 45 mins long, and the irony of a precocious teenager teaching some life lessons to an older woman is evident even before the big reveal halfway through: that the woman is in fact a teacher at the boy’s school. A second irony is added when the teacher is hounded out of her job by false allegations of seducing a student. The repercussions of that accusation is what puts her in danger of seducing a student for real.

These ironies don’t lead anywhere, and perhaps they don’t have to. Watching this after Your Name, it’s evident that Shinkai has an interest in star-crossed lovers brought together and torn apart by fate, a force given an almost physical presence by the photorealistic hyperreal animation. It’s manipulative – a reliance on these tricks is why I dislike Wong Kai-Wai so much. For some reason, Shinaki’s equivalent is more tolerable, perhaps because we get under the skin of his characters to a greater extent than the detached cool of Wong’s lost urbanites.

Like Your Name, The Garden of Words ends on two characters on a set of stairs finally recognising each other. It’s a climax that Wong refuses to grant his viewers, and his films end up feeling emptier as a result. This, on the other hand, is generous, well-paced, and satisfying, despite the open-ended finale.

These ironies don’t lead anywhere, and perhaps they don’t have to. Watching this after Your Name, it’s evident that Shinkai has an interest in star-crossed lovers brought together and torn apart by fate, a force given an almost physical presence by the photorealistic hyperreal animation. It’s manipulative – a reliance on these tricks is why I dislike Wong Kai-Wai so much. For some reason, Shinaki’s equivalent is more tolerable, perhaps because we get under the skin of his characters to a greater extent than the detached cool of Wong’s lost urbanites.

Like Your Name, The Garden of Words ends on two characters on a set of stairs finally recognising each other. It’s a climax that Wong refuses to grant his viewers, and his films end up feeling emptier as a result. This, on the other hand, is generous, well-paced, and satisfying, despite the open-ended finale.

16.2.18

Samurai Champloo

If this makes any sense at all, it's as metaphor. One sword-wielding badass represents order and the other chaos, with the girl in the middle providing the semblance of a quest narrative. Jin follows the rules of the samurai genre while Mugen breaks them. Jin comes straight out of the Edo period and Mugen is a break-dancing hip-hop rebel. Jin is the samurai and Mugen the champloo. They are eternal and immutable opposing forces destined to orbit the female protagonist as she pursues her goal. And instead of resolution the series offers equilibrium. Backstory or progression rarely intrude on each bottle episode's brawls and scrapes.

So far so good, but the three-part finale has to lead somewhere. Fuu is the girl who yokes Jin and Mugen together to look for what turns out to be her father, who abandoned her and her mother when Fuu was a child. The idea of a patriarch who has deserted his responsibilities hangs over our angsty trio – kids without a sense of purpose or direction. The absent father may stand in for a defeated nation, destabalised gender roles, a precarious economy... you name it. Fuu is chasing the good-for-nothing bastard in order to slug him one for his dereliction of duty.

Except that in the end her father was trying to protect her all along. He did behave honourably. He did love his child. Her rage was misplaced. It's interesting that Fuu's ability to strike out on what turns out to be an extremely dangerous journey is powered by that sense of injustice, but the anime keeps stuffing this independent spirit back in the box. Because it turns out that Fuu needs Jin and Mugen, her incompetent bodyguards, to protect her on the way to her confrontation with her father. She simply cannot get by without them. The anime teases the concept of an independent woman only to put her in need of saving again and again. And in doing so, the patriarchy is redeemed.

The ending is therefore reassuring, conservative, and happy. At least there aren't any marriages. There are hints of a romantic triangle, but the anime ends by stressing the friendship between the three heroes. Their quest complete, their bonds affirmed, their demons purged, they go their separate ways. Such elemental forces are destined to wander rather than settle down. The anime is at root a chronicle of their journey together. It's only fitting that it should end when that particular journey is over.

So far so good, but the three-part finale has to lead somewhere. Fuu is the girl who yokes Jin and Mugen together to look for what turns out to be her father, who abandoned her and her mother when Fuu was a child. The idea of a patriarch who has deserted his responsibilities hangs over our angsty trio – kids without a sense of purpose or direction. The absent father may stand in for a defeated nation, destabalised gender roles, a precarious economy... you name it. Fuu is chasing the good-for-nothing bastard in order to slug him one for his dereliction of duty.

Except that in the end her father was trying to protect her all along. He did behave honourably. He did love his child. Her rage was misplaced. It's interesting that Fuu's ability to strike out on what turns out to be an extremely dangerous journey is powered by that sense of injustice, but the anime keeps stuffing this independent spirit back in the box. Because it turns out that Fuu needs Jin and Mugen, her incompetent bodyguards, to protect her on the way to her confrontation with her father. She simply cannot get by without them. The anime teases the concept of an independent woman only to put her in need of saving again and again. And in doing so, the patriarchy is redeemed.

The ending is therefore reassuring, conservative, and happy. At least there aren't any marriages. There are hints of a romantic triangle, but the anime ends by stressing the friendship between the three heroes. Their quest complete, their bonds affirmed, their demons purged, they go their separate ways. Such elemental forces are destined to wander rather than settle down. The anime is at root a chronicle of their journey together. It's only fitting that it should end when that particular journey is over.

16.9.17

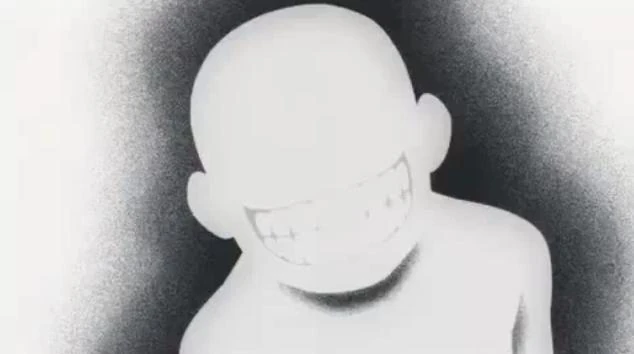

Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood

It's probably inevitable that a story about alchemy with a happy ending must involve the renunciation of pride and ambition. Much like Frankenstein or Faust, alchemists dabble in forbidden knowledge and are punished for it. The big bad in this anime series wants to know all the secrets of the universe and live forever – usurp God's rightful place. God is having none of it however. The anime portrays him as a grinning white human outline, and he condemns the pretender to his throne to eternal despair. On the other hand, our hero Edward Elric renounces his genius for alchemy with the claim that self worth is not bought with knowledge but is conferred by one's peers – your family and friends. The grinning God is well pleased with this answer, and rewards Edward by returning his brother Alphonse from death.

This theological condemnation of human curiosity feels rather old-fashioned in the gnosticism-infused times we live in, where the Fall of Mankind is spun as a positive development à la His Dark Materials. Fullmetal Alchemist is a bit more Raiders of the Lost Arc – peering into the holy of holies will melt your face. It's also a bit weird that after apprehending the big truth that we are limited, foolish creatures who don't deserve enlightenment, Edward leaves his family and friends again at the end of the series chasing after more knowledge. The anime glamourises lone questing male heroes who must abandon their partners and children in the process of said quest... all while talking up how family is the preferred avenue of fulfilment.

But leaving these contradictions aside, the series is very good at exploring the consequences of ambition, both in the way it reduces people to a means to an end (philosopher stones are literally products of genocide), and also in the suffering left in its wake. The anime is set after the events of a brutal war against dark-skinned, red-eyed Ishvalans. In the original manga, this was a comment on the displaced Ainu of Japan. In Brotherhood it's easier to draw parallels with more recent conflict in the Middle East. What is interesting is that the purported 'good guys' have very clearly committed atrocities in the past. Likewise the most prominent Ishvalan character starts out as a terrorist, a religious zealot, and a murderer of innocents. Despite perpetrating unforgivable crimes, both he and his oppressors are given a shot at redemption, and an opportunity to reconstruct their war-ravaged societies.

This doveish theme is undercut slightly by the very prominent fascistic iconography employed by the series. The country is ruled by a Fuhrer, the setting is an alternate version of early 20th century central Europe where democracy is crumbling, and service to your commanding officer is presented in glowing terms. Roy Mustang, who emerges as the new Fuhrer at the end of the show, has as his guiding philosophy the paternalistic notion that if he looks after his subordinates, and they look after their subordinates, well-being will filter down to the country at large. Of course setting an example is important, but the checks and balances of a functioning republic only get a cursory mention, and I know which I'd rather rely on.

In any case, Brotherhood is not immune to the trope of government conspiracies, corruption and factional infighting frequently found in depictions of politics in Japanese media. Edward Elric's impetuous irreverence is the only protest levelled at the inevitability of these shenanigans, and it's an impotent one. The wheels of the machine keep turning, and resignation (like that of Edward's father) appears to be the only mature response.

It's very watchable, of course. Game of Thrones fans have no right to sneer at it (or to ever talk about fan service). Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood is often more harrowing, but also infinitely funnier than George R.R. Martin's grim fantasy. Also, at 64 half-hour episodes, is more digestible and compressed than Game of Thrones. I was particularly impressed with the very tight plotting of the initial episodes, where a great deal of information is crammed in. The series slows down and stretches out as it goes on, to the point where the climactic final day goes on for something like 10 episodes. But the action never slows down, and my interest never faltered. It's an accomplished performance throughout, and well worth your time.

This theological condemnation of human curiosity feels rather old-fashioned in the gnosticism-infused times we live in, where the Fall of Mankind is spun as a positive development à la His Dark Materials. Fullmetal Alchemist is a bit more Raiders of the Lost Arc – peering into the holy of holies will melt your face. It's also a bit weird that after apprehending the big truth that we are limited, foolish creatures who don't deserve enlightenment, Edward leaves his family and friends again at the end of the series chasing after more knowledge. The anime glamourises lone questing male heroes who must abandon their partners and children in the process of said quest... all while talking up how family is the preferred avenue of fulfilment.

But leaving these contradictions aside, the series is very good at exploring the consequences of ambition, both in the way it reduces people to a means to an end (philosopher stones are literally products of genocide), and also in the suffering left in its wake. The anime is set after the events of a brutal war against dark-skinned, red-eyed Ishvalans. In the original manga, this was a comment on the displaced Ainu of Japan. In Brotherhood it's easier to draw parallels with more recent conflict in the Middle East. What is interesting is that the purported 'good guys' have very clearly committed atrocities in the past. Likewise the most prominent Ishvalan character starts out as a terrorist, a religious zealot, and a murderer of innocents. Despite perpetrating unforgivable crimes, both he and his oppressors are given a shot at redemption, and an opportunity to reconstruct their war-ravaged societies.

This doveish theme is undercut slightly by the very prominent fascistic iconography employed by the series. The country is ruled by a Fuhrer, the setting is an alternate version of early 20th century central Europe where democracy is crumbling, and service to your commanding officer is presented in glowing terms. Roy Mustang, who emerges as the new Fuhrer at the end of the show, has as his guiding philosophy the paternalistic notion that if he looks after his subordinates, and they look after their subordinates, well-being will filter down to the country at large. Of course setting an example is important, but the checks and balances of a functioning republic only get a cursory mention, and I know which I'd rather rely on.

In any case, Brotherhood is not immune to the trope of government conspiracies, corruption and factional infighting frequently found in depictions of politics in Japanese media. Edward Elric's impetuous irreverence is the only protest levelled at the inevitability of these shenanigans, and it's an impotent one. The wheels of the machine keep turning, and resignation (like that of Edward's father) appears to be the only mature response.

It's very watchable, of course. Game of Thrones fans have no right to sneer at it (or to ever talk about fan service). Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood is often more harrowing, but also infinitely funnier than George R.R. Martin's grim fantasy. Also, at 64 half-hour episodes, is more digestible and compressed than Game of Thrones. I was particularly impressed with the very tight plotting of the initial episodes, where a great deal of information is crammed in. The series slows down and stretches out as it goes on, to the point where the climactic final day goes on for something like 10 episodes. But the action never slows down, and my interest never faltered. It's an accomplished performance throughout, and well worth your time.

6.5.17

Cowboy Bebop: The Movie

An exercise in style, mostly. I haven't watched the series, but given that the characters are just collections of archetypes, it's very easy to catch up and get into the swing of things. The animation is brilliant – particularly in its use of distorted perspective and skewed framing. And the music choices are inspired – a selection of jazz and funk tracks that bring the science fiction setting down to earth, and highlight the debts owed to hard-boiled noir. The characters are all flamboyantly-dressed Tarantino-esque smart-mouths (although the film does tend to disrobe the women to telegraph their vulnerability).

Piecing together what the film is about is an unhappy task. There is something to its notion that being free from the fear of death is the source of true liberty. It also seems to be the source of the main character's exhilarating martial arts and piloting abilities. An almost Buddhist renunciation of worldly attachments is married to the rugged individualism of the wild west.

The villain is the victim of a corporate conspiracy, who wants to share the pain he has been put through by releasing a chemical weapon in the middle of a city parade (parallels with the Sarin attacks in Tokyo are left unexplored). As is typical in anime, the corporation does not get its comeuppance at the end (in contrast to the new Ghost in the Shell film, for example). Instead the only way out is suicide, of a sort. The filmmakers link this death drive to a sense of the numinous and transcendent, and end by asking the audience if they can tell what's real and what's make believe. The villain and hero are mirror images of each other, and the film may be warning the audience away from the alluring but nihilistic aesthetic they embody.

Piecing together what the film is about is an unhappy task. There is something to its notion that being free from the fear of death is the source of true liberty. It also seems to be the source of the main character's exhilarating martial arts and piloting abilities. An almost Buddhist renunciation of worldly attachments is married to the rugged individualism of the wild west.

The villain is the victim of a corporate conspiracy, who wants to share the pain he has been put through by releasing a chemical weapon in the middle of a city parade (parallels with the Sarin attacks in Tokyo are left unexplored). As is typical in anime, the corporation does not get its comeuppance at the end (in contrast to the new Ghost in the Shell film, for example). Instead the only way out is suicide, of a sort. The filmmakers link this death drive to a sense of the numinous and transcendent, and end by asking the audience if they can tell what's real and what's make believe. The villain and hero are mirror images of each other, and the film may be warning the audience away from the alluring but nihilistic aesthetic they embody.

4.3.17

Ice

A post-apocalyptic anime film with a premise similar to Children of Men, but with a curious gender twist – only male babies stop being born. In the all-female society that emerges in the ruins of Tokyo, masculinity is associated with militarism and the hubris of science – the two forces that led to the unspecified natural disaster or war that has transformed the planet. Soldiers demure from using handguns, which are perceived as dangerously 'male' weapons.

On the one hand, charges of essentialism are avoided by having a villain tempted by the same 'masculine' forces her society abhors – Julia wants to use abandoned technology to remake the world again. On the other hand, both Juila and the hero Hitomi are presented as very masculine women – in terms of wardrobe, hairstyles and voice. Hitomi is much like other brooding, self-sufficient, celibate male protagonists in anime, and Julia is much like other decadent and depraved male antagonists. The 'female' female characters in the film are invariably of lower rank, less skilled, and have fewer opportunities to display any kind of agency.

The film's environmental message is rather heavy-handed. A memorable instance of body horror is used to disparage the idea of genetic engineering. There is also the rather strange conceit of Hitomi being haunted by the spirit of a girl from 'our' pre-apocalyptic world, who wakes up at the end convinced to change her polluting ways.

It is a rather weird concoction – as with a lot of anime, the plot zips along and compresses a huge amount of information at the start. The overload means you spend much of the film befuddled and unsure of why things are happening. But as a vehicle for extravagant, surreal images of the future, it's rather effective. There are some quite beautiful visual sequences in the film, not least the strange scene of birds transforming into plants and trees. At points you get that sense of future shock from seeing a completely alien civilisation comparable to something like Frank Herbert's Dune. That makes it worth seeing, despite the questionable gender politics.

On the one hand, charges of essentialism are avoided by having a villain tempted by the same 'masculine' forces her society abhors – Julia wants to use abandoned technology to remake the world again. On the other hand, both Juila and the hero Hitomi are presented as very masculine women – in terms of wardrobe, hairstyles and voice. Hitomi is much like other brooding, self-sufficient, celibate male protagonists in anime, and Julia is much like other decadent and depraved male antagonists. The 'female' female characters in the film are invariably of lower rank, less skilled, and have fewer opportunities to display any kind of agency.

The film's environmental message is rather heavy-handed. A memorable instance of body horror is used to disparage the idea of genetic engineering. There is also the rather strange conceit of Hitomi being haunted by the spirit of a girl from 'our' pre-apocalyptic world, who wakes up at the end convinced to change her polluting ways.

It is a rather weird concoction – as with a lot of anime, the plot zips along and compresses a huge amount of information at the start. The overload means you spend much of the film befuddled and unsure of why things are happening. But as a vehicle for extravagant, surreal images of the future, it's rather effective. There are some quite beautiful visual sequences in the film, not least the strange scene of birds transforming into plants and trees. At points you get that sense of future shock from seeing a completely alien civilisation comparable to something like Frank Herbert's Dune. That makes it worth seeing, despite the questionable gender politics.

2.12.16

Your Name

I've previously been a bit harsh on Matoko Shinkai. Your Name doesn't abandon the romantic longing of 5 Centimeters Per Second, but the angst is worn more lightly, and the characters feel less like ciphers. The animation is also more restrained – the night skies no longer look like Rainbow Road in Mario Kart, and there is a rather cool dream sequence which swaps crisp photorealism for a more flowing, sketched style.

The plot, as with many a time travel story, breaks apart the more you prod at it. But the conceit of two teenagers switching bodies is employed well. Shinkai has said that some of the town vs country stuff comes from his own experience of growing up. More important for me, however, is the way inhabiting another person's life becomes a metaphor for falling in love. Because being in a relationship is sort of like that. You gain access to memories of things you didn't experience at first hand. You learn about a childhood different from your own, with a new family and set of friends. You also get to know someone else's body in intimate detail (a source of some of the film's funniest moments). And by becoming comfortable in each other's skins, the two characters find that they cannot live happily without each other.

This is eked out a bit in the final part of the film, where Shinkai contrives to separate his heroes, and have them morosely wander around Tokyo searching for their other halves. But it serves to highlight how draining the loss of such a person might be, and it leads to a very satisfying finale.

The plot, as with many a time travel story, breaks apart the more you prod at it. But the conceit of two teenagers switching bodies is employed well. Shinkai has said that some of the town vs country stuff comes from his own experience of growing up. More important for me, however, is the way inhabiting another person's life becomes a metaphor for falling in love. Because being in a relationship is sort of like that. You gain access to memories of things you didn't experience at first hand. You learn about a childhood different from your own, with a new family and set of friends. You also get to know someone else's body in intimate detail (a source of some of the film's funniest moments). And by becoming comfortable in each other's skins, the two characters find that they cannot live happily without each other.

This is eked out a bit in the final part of the film, where Shinkai contrives to separate his heroes, and have them morosely wander around Tokyo searching for their other halves. But it serves to highlight how draining the loss of such a person might be, and it leads to a very satisfying finale.

24.9.16

Perfect Blue

“…after going back

and forth between the real world and the virtual world you eventually find your

own identity through your own powers. Nobody can help you do this. You are

ultimately the only person who can truly find a place where you know you belong.”

That’s Satoshi Kon on the anime, his first feature as a

director. It’s essentially a slasher film in which the victim and predator are

split personalities vying for control over the main character, the latter

drifting out to possess other bodies and use them as weapons. What’s real and

what isn’t is kept intentionally vague, but it’s also somewhat beside the

point. What Kon is really interested in is the way we find out who we really

want to be in the maze of media and culture we consume.

The protagonist Mima is a 'pop idol' who wants to become

a serious actress. Her fan base is exclusively comprised of young men who are

attached to her pure, pleasant and infantile persona. Her career is managed by

an agency, mostly men again telling her what to do. But the choice to become an

actress is her own. It is a chance to grow up, but it will also disappoint her

fans, who expect her to play one particular role, rather than many. An irony

the film touches on (but doesn’t explore enough) is that in transitioning from her

image of the virgin, Mima is almost inevitably cast as a whore. It seems there

are only so many roles available, although Kon might be suggesting that more avenues

become open once the teen idol fantasy is abandoned for a more adult (in every sense of the word) persona.

The decision to become an actress leads to a crisis – a part

of Mima’s psyche rebels and seeks revenge for her own disgrace, murdering the

scriptwriter who wrote her into a rape scene and the photographer who persuaded her to pose nude for a magazine shoot. The slasher wants to give the fans what

they want, and crush Mima’s attempts to become her own person. She is a

manifestation of the urge to go back and have your life controlled by other

people.

The film is an efficient thriller, spending some time at the

beginning establishing Mima’s character before gradually pulling apart her

sense of reality. The tension rises as the bodies pile up, and good use is made

of the eeriness of a sugar-sweet sprite being responsible for a variety of brutal

stabbings. It feels like a more linear and focused work that Paprika (the only other Kon anime I’ve

seen). And it’s a more satisfying exploration of the struggle to assert your

identity in a mass media society – which amplifies rather than dissipates the

expectations people have of what your ideal self should be.

10.9.16

5 Centimeters Per Second

"...if you look at our everyday lives, you realise that we're well-fed, well-clothed and well-housed. We also live in a society where there's almost no class discrimination. And we have freedom to live our lives however we want. Considering what kind of society we live in, if you still have problems with relationships with people, the cause of the problem is probably not society or anything readily apparent. In that case, you have to find the cause within yourself. That's actually a hard thing to do, I think. You might think there's a nothing within you that's causing the problem. So I had a strong desire to portray that 'nothingness' as it is."

That's the director Makoto Shinkai on the film. No doubt he's somewhat blinkered in his view that society places almost no restrictions on our liberty. That kind of complacency is frustrating, but the myopia runs deeper. The truth is, trying to isolate the cause of your discontent without reference to the expectations placed on you by others is a mug's game. That's why the characters in this film feel more like archetypes role-playing doomed love affairs rather than real people. Takaki is little more than a dreamy heartthrob yearning to protect Akari from the evils of the world. Their drifting apart is the product of the cold mathematics of speed and distance – their families move away, it's too far for them to continue their relationship. It's as simple and as brutal as that.

The real highlight is Kanae in the second 'Act' of the film – the only time it adopts a female perspective. She also pines after the cool Takaki, and formulates her life-projects with reference to his own. That leaves her in limbo when she realises that he will never be interested in her. In fact, her one moment of glory comes when she achieves something on her own – learning how to surf from her older sister. That victory is clouded by her subsequent rejection, but it points to the damage caused when tying up all your self-worth onto the whims of another person.

There is another highlight, of course – the dazzling imagery. Every frame of the anime is polished to a brilliant sheen, sometimes to the point of distraction, particularly when it comes to the nebula-stuffed starry skies. The animation is more impressive when it comes to the everyday details of train stations, convenience stores and countryside roads, which capture the look and feel of Japan unbelievably well. It's those wonderfully realised bits of quotidian existence that add a weight to the otherwise fluffy angst the film is portraying. It's a shame that for all his efforts to embed them in the real world, Shinkai can't make his characters actually feel real.

That's the director Makoto Shinkai on the film. No doubt he's somewhat blinkered in his view that society places almost no restrictions on our liberty. That kind of complacency is frustrating, but the myopia runs deeper. The truth is, trying to isolate the cause of your discontent without reference to the expectations placed on you by others is a mug's game. That's why the characters in this film feel more like archetypes role-playing doomed love affairs rather than real people. Takaki is little more than a dreamy heartthrob yearning to protect Akari from the evils of the world. Their drifting apart is the product of the cold mathematics of speed and distance – their families move away, it's too far for them to continue their relationship. It's as simple and as brutal as that.

The real highlight is Kanae in the second 'Act' of the film – the only time it adopts a female perspective. She also pines after the cool Takaki, and formulates her life-projects with reference to his own. That leaves her in limbo when she realises that he will never be interested in her. In fact, her one moment of glory comes when she achieves something on her own – learning how to surf from her older sister. That victory is clouded by her subsequent rejection, but it points to the damage caused when tying up all your self-worth onto the whims of another person.

There is another highlight, of course – the dazzling imagery. Every frame of the anime is polished to a brilliant sheen, sometimes to the point of distraction, particularly when it comes to the nebula-stuffed starry skies. The animation is more impressive when it comes to the everyday details of train stations, convenience stores and countryside roads, which capture the look and feel of Japan unbelievably well. It's those wonderfully realised bits of quotidian existence that add a weight to the otherwise fluffy angst the film is portraying. It's a shame that for all his efforts to embed them in the real world, Shinkai can't make his characters actually feel real.

10.7.16

Ninja Scroll

This 1993 anime gets grouped alongside Ghost in the Shell and Akira as being classics reasonably well-known in the West. It's an expertly crafted wuxia (martial arts) film, with very stylish and frequently gruesome fight scenes, a complex story which unfolds well, and every narrative thread tied up nicely at the end. That doesn't distract from the sometimes rather troubling genre conventions it exemplifies. As expected, the hero Jubei is an itinerant warrior who refuses to play by anyone's rules but his own – a particularly attractive fantasy for conformist Japan. His attitude echoes that of Guts in the manga Berserk, who feels nothing but disdain for those too weak to avoid exploitation.

But exploitation is inevitable in the world of Ninja Scroll. Jubei is forcibly recruited by a wizened, wry (and unexpectedly wiry) government spy as a foot soldier in a secret war between the Tokugawa Shogunate and a rebellious lord (the so-called 'Shogun of the Dark'). Neither side in the conflict are particularly noble – all elites in feudal Japan use, abuse and discard those lower down the social hierarchy. But interestingly, rather than struggling against the evil empire, our protagonist's role is to protect it from something worse – factionalism and the civil war that raged before Tokugawa Ieyasu defeated all comers and established his regime. The film reinforces the notion that you will be chewed up and spat out by those above your station, and that this is a price worth paying. No matter how individualistic these ronin are, they can't escape co-option by the political powers that be.

And then there's the women. Jubei crosses paths with a feisty poison-taster and clandestine ninja called Kagero – rescuing her from being raped by the first of what turn out to be eight superpowered adversaries. The poisons Kagero has imbibed mean she is unable to sleep with, or even kiss, someone without them dying. Her independence and fighting prowess is bought at the expense of a complete neutering of her sexuality. Rather unbelievably, it turns out that Jubei can and must seduce Kagero in order to neutralise the poison he has been infected with. His relationship with her for the most part of the film is huffy and disrespectful, but he is nonetheless steely enough to refuse to sleep with her on these terms, choosing death before dishonour. Celibacy is the route to heroism for both characters, even though both (particularly Kagero) are objectified and sexualised to some degree.

This is in marked contrast to the bad guys, of course, who all seem to be sleeping with each other. And not just with the opposite sex either, which adds an extra homophobic tang to proceedings...

But exploitation is inevitable in the world of Ninja Scroll. Jubei is forcibly recruited by a wizened, wry (and unexpectedly wiry) government spy as a foot soldier in a secret war between the Tokugawa Shogunate and a rebellious lord (the so-called 'Shogun of the Dark'). Neither side in the conflict are particularly noble – all elites in feudal Japan use, abuse and discard those lower down the social hierarchy. But interestingly, rather than struggling against the evil empire, our protagonist's role is to protect it from something worse – factionalism and the civil war that raged before Tokugawa Ieyasu defeated all comers and established his regime. The film reinforces the notion that you will be chewed up and spat out by those above your station, and that this is a price worth paying. No matter how individualistic these ronin are, they can't escape co-option by the political powers that be.

And then there's the women. Jubei crosses paths with a feisty poison-taster and clandestine ninja called Kagero – rescuing her from being raped by the first of what turn out to be eight superpowered adversaries. The poisons Kagero has imbibed mean she is unable to sleep with, or even kiss, someone without them dying. Her independence and fighting prowess is bought at the expense of a complete neutering of her sexuality. Rather unbelievably, it turns out that Jubei can and must seduce Kagero in order to neutralise the poison he has been infected with. His relationship with her for the most part of the film is huffy and disrespectful, but he is nonetheless steely enough to refuse to sleep with her on these terms, choosing death before dishonour. Celibacy is the route to heroism for both characters, even though both (particularly Kagero) are objectified and sexualised to some degree.

This is in marked contrast to the bad guys, of course, who all seem to be sleeping with each other. And not just with the opposite sex either, which adds an extra homophobic tang to proceedings...

20.4.15

Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence

Mamoru Oshii's sequel to the phenomenally successful Ghost in the Shell, which I praise to the skies here. This second film departs quite a bit from Shirow Masamune's original manga, and feels quite personal to the director. But Oshii is an inscrutable guy, insisting that he doesn't interpret his films until after they are made. And his obsession with realising visual ideas clearly overshadows concerns with plot, theme and character. The festival sequence took a year to make apparently, and I'm not sure it's more powerful than Kusanagi wandering around the city in the first film.

So making sense of Innocence is a tricky task, but let's give it a go. Batou takes centre stage for this one, with Kusanagi serving as his 'guardian angel' – intervening only when he's in a really sticky situation. Quite a bit of time is spent exploring Batou's loneliness, and his relationship with his dog. The film circles around the idea of humanity's interest in creating human-like robots, without really confronting it head on. The villains in the film manufacture sex-dolls with the implanted 'ghosts' (or souls) of children. Batou's dog, according to Oshii, is also a creature manufactured by humans to serve as companions. But it is nonetheless an animal and different to ourselves. And that difference is a reminder of our uniqueness. We would never feel that lack we feel with a human-shaped doll or robot, which spurs us towards greater feats of Frankensteinian creation. Controversially, Oshii seems to suggest that pets may keep us more grounded than our own children, who we are always trying to mould in our own image.

Oshii's ideas are a bit garbled, but he is clearly committed to the importance of treating sentient beings as ends in themselves, with their own equally valuable interests and attachments. Our urge to make the outside world a reflection of ourselves, and shape the reality of others, is what seems to worry Oshii. Ironically, he describes the film-making process in very similar terms – expressing the psychology of different characters visually, through the look and feel of a futuristic cityscape or mysterious ritual. Oshii clearly works his animators very hard to fulfill his vision. It's almost as if his will-to-power is siphoned away from the real world and into harmless works of art.

So making sense of Innocence is a tricky task, but let's give it a go. Batou takes centre stage for this one, with Kusanagi serving as his 'guardian angel' – intervening only when he's in a really sticky situation. Quite a bit of time is spent exploring Batou's loneliness, and his relationship with his dog. The film circles around the idea of humanity's interest in creating human-like robots, without really confronting it head on. The villains in the film manufacture sex-dolls with the implanted 'ghosts' (or souls) of children. Batou's dog, according to Oshii, is also a creature manufactured by humans to serve as companions. But it is nonetheless an animal and different to ourselves. And that difference is a reminder of our uniqueness. We would never feel that lack we feel with a human-shaped doll or robot, which spurs us towards greater feats of Frankensteinian creation. Controversially, Oshii seems to suggest that pets may keep us more grounded than our own children, who we are always trying to mould in our own image.

Oshii's ideas are a bit garbled, but he is clearly committed to the importance of treating sentient beings as ends in themselves, with their own equally valuable interests and attachments. Our urge to make the outside world a reflection of ourselves, and shape the reality of others, is what seems to worry Oshii. Ironically, he describes the film-making process in very similar terms – expressing the psychology of different characters visually, through the look and feel of a futuristic cityscape or mysterious ritual. Oshii clearly works his animators very hard to fulfill his vision. It's almost as if his will-to-power is siphoned away from the real world and into harmless works of art.

1.12.13

Ghost in the Shell

The anime, which I've loved for a long time, is taut but very dense, and it's difficult to appreciate all its details just in one sitting. That said, its basic theme is easy enough to glean from the title, a riff on the idea of the ghost in the machine, the inner enlivening spirit which separates man from the rest of the mechanical universe. When our cyborg hero, Major Kusanagi, is confronted by an A.I. (the "Puppet Master") who declares itself to be a sentient, rights-bearing life-form, she starts to wonder whether she is any different for having a few brain cells remaining in her cortex. She asks Batou whether she is human simply because of the way she is treated: a social convention that the Puppet Master will undermine.

The manga, which I've read only recently, includes a notes section at the back where the author not only gives background, but explains the ground, since the plotting is even more tangled and inscrutable than in the film. Masamune Shirow is a very frustrating guide to his own creation, coming across as an excitable autodidact who mashes and remixes a heap of memes, but who's ability to synthesise and explain his arguments has gone AWOL. Part of the problem may be that he lives in his world so deeply that he assumes the reader already understands most of it. The notes are fascinating nonetheless, particularly when they leave behind all the talk of "ordinance and equipment" and start to cover the concept of ghosts and the influence of religion on his work:

The thing about pantheism is that when you push it out enough it starts to look like atheism. Shirow's manga is suffused with his idiosyncratic musings on the way technology and the world of the spirit intermingle, but his inclusion of the idea of a machine that can generate its own ghost introduces a destabalising element to the cosmic order: where do you find Cartesian dualism if everything has its very own ghost, including our computers? Do we not then jettison the spirit world altogether for the sake of simplicity? Shirow is too wedded to his systems and phases to accept this, and he continues to believe in channelers and psychics. The anime, however, is more ambiguous, which is partly why it is one of the rare cases where an adaptation improves on the original.

The actual title of the manga translates as Mobile Armored Riot Police, and the philosophical stuff is definitely a side-order to the main course of running, jumping, shooting and intrigue. The anime chooses the subtitle of the manga as its title, and flips the focus onto the existential crisis of its hero. Its pacing is deliberately slow-fast: kinetic pieces of action are followed by languorous sequences where the Major dreams of her robotic rebirth and then relives that dream by floating on the ocean. The Puppet Master chooses her as his mate because they are alike. "He" is a program used for corporate espionage trying to escape his masters. She is an assassin who's body and soul is owned by the corporation that made it (one that dictates she has to be naked in order for her invisibility to function). In the middle of the film there is an at-first bewilderingly long set-piece where she wanders New Port City, soundtracked by a Japanese choir (borrowing the harrowing vocal tones of Bulgarian folk music). The metropolitan anomie is given a cybernetic gloss as the sequence ends on a shot of shop window mannequins. Kusanagi dreams of a new life beyond the borders of this one, just as the Puppet Master desires a life beyond the networks he traverses.

At the beginning of the film, Kusanagi explains the dangers of specialisation to a new recruit, saying that unpredictability and adaptation are necessary to make the unit stronger. The Puppet Master uses the same arguments at the end to convince Kusanagi into a sexual (in the biological sense) union. Rather than living forever and reproducing endless copies of himself, he desires a dynamic system where death and difference is the norm. The film overlays this fusion with sexual, violent and religious imagery. Sex inevitably entails death, as it is the activity that allows for our replacement. Just before the union is complete, Kusanagi witnesses an angel descending over her, blessing the new bond. The sense is that they have both transitioned into a higher order system, that much closer to the gods. But it is just as easy to read this as the machine not only generating its own ghost, but a sense of the numinous humans have evolved with.

That final showdown between the Major and the tank is not set to a thumping techno soundtrack. Instead, it speeds up the juxtaposition of kinetic and meditative scenes running through the film, and overlays it with mellow flute washes evoking the immemorial past. It is a samurai duel in the 21st century, set against the backdrop of a phylogenetic tree of life, shot to pieces by modern machinery. The symbolic richness on display is characteristic of the film, in which every element – the voice in the lake, the three different cases (which are three different chapters in the manga) – is weaved together in ways only multiple viewings can unravel. That mixture of depth and directness is what makes it a great film.

The manga, which I've read only recently, includes a notes section at the back where the author not only gives background, but explains the ground, since the plotting is even more tangled and inscrutable than in the film. Masamune Shirow is a very frustrating guide to his own creation, coming across as an excitable autodidact who mashes and remixes a heap of memes, but who's ability to synthesise and explain his arguments has gone AWOL. Part of the problem may be that he lives in his world so deeply that he assumes the reader already understands most of it. The notes are fascinating nonetheless, particularly when they leave behind all the talk of "ordinance and equipment" and start to cover the concept of ghosts and the influence of religion on his work:

"I think all things in nature have "ghosts". This is a form of pantheism, and similar to ideas found in Shinto or among believers in the Manitou. Because of the complexity and function, and the physical constraints they have when they appear as a physical phenomenon, it may be impossible to scientifically prove this. There are, after all, humans who act more like robots than robots, and no one can say for certain that they have no ghosts just because they don't act like it. In ancient times, neither air nor the universe were believed to exist."I've included wikipedia links in the above, and only a brief scan will confirm that these are vastly different traditions Shirow is referencing here. What's clear is that he believes in a kind of cosmic ordering in which spirits can influence our lives. This carries over into the anime: the Major sometimes hears "whispers" in her ghost, a preternatural intuition that tells her which car to tail, for example. All humans have a "ghost line", a baseline piece of information or energy you can "dive" into (read) or hack (write), which separates them from other pieces of software.

The thing about pantheism is that when you push it out enough it starts to look like atheism. Shirow's manga is suffused with his idiosyncratic musings on the way technology and the world of the spirit intermingle, but his inclusion of the idea of a machine that can generate its own ghost introduces a destabalising element to the cosmic order: where do you find Cartesian dualism if everything has its very own ghost, including our computers? Do we not then jettison the spirit world altogether for the sake of simplicity? Shirow is too wedded to his systems and phases to accept this, and he continues to believe in channelers and psychics. The anime, however, is more ambiguous, which is partly why it is one of the rare cases where an adaptation improves on the original.

The actual title of the manga translates as Mobile Armored Riot Police, and the philosophical stuff is definitely a side-order to the main course of running, jumping, shooting and intrigue. The anime chooses the subtitle of the manga as its title, and flips the focus onto the existential crisis of its hero. Its pacing is deliberately slow-fast: kinetic pieces of action are followed by languorous sequences where the Major dreams of her robotic rebirth and then relives that dream by floating on the ocean. The Puppet Master chooses her as his mate because they are alike. "He" is a program used for corporate espionage trying to escape his masters. She is an assassin who's body and soul is owned by the corporation that made it (one that dictates she has to be naked in order for her invisibility to function). In the middle of the film there is an at-first bewilderingly long set-piece where she wanders New Port City, soundtracked by a Japanese choir (borrowing the harrowing vocal tones of Bulgarian folk music). The metropolitan anomie is given a cybernetic gloss as the sequence ends on a shot of shop window mannequins. Kusanagi dreams of a new life beyond the borders of this one, just as the Puppet Master desires a life beyond the networks he traverses.

At the beginning of the film, Kusanagi explains the dangers of specialisation to a new recruit, saying that unpredictability and adaptation are necessary to make the unit stronger. The Puppet Master uses the same arguments at the end to convince Kusanagi into a sexual (in the biological sense) union. Rather than living forever and reproducing endless copies of himself, he desires a dynamic system where death and difference is the norm. The film overlays this fusion with sexual, violent and religious imagery. Sex inevitably entails death, as it is the activity that allows for our replacement. Just before the union is complete, Kusanagi witnesses an angel descending over her, blessing the new bond. The sense is that they have both transitioned into a higher order system, that much closer to the gods. But it is just as easy to read this as the machine not only generating its own ghost, but a sense of the numinous humans have evolved with.

That final showdown between the Major and the tank is not set to a thumping techno soundtrack. Instead, it speeds up the juxtaposition of kinetic and meditative scenes running through the film, and overlays it with mellow flute washes evoking the immemorial past. It is a samurai duel in the 21st century, set against the backdrop of a phylogenetic tree of life, shot to pieces by modern machinery. The symbolic richness on display is characteristic of the film, in which every element – the voice in the lake, the three different cases (which are three different chapters in the manga) – is weaved together in ways only multiple viewings can unravel. That mixture of depth and directness is what makes it a great film.

19.4.13

Sky Blue

A Korean anime film that (according to the back cover) took 7 years to make. The wikipedia entry focuses almost entirely on its technical achievements: photo-realistic CGI, rendered vehicles, cel animated characters. It looks as impressive as it sounds, at least I think so, but I grew up on the thrill of computer game cut-scenes. What's equally impressive is the attempt (if not the achievement) of a political message. Ecoban is a city-state run by callous philosopher kings and supported by a serf population kept outside its shielded walls. One particularly nasty member of the elect is called Locke, perhaps a nod to the property-loving 17th century liberal philosopher (although if people knew their history they would be more inclined to place him on the side of the revolutionaries). The leader of the copper class is called Noah, and wouldyabelieveit he lives in a boat, enduring the unceasing rain and planning for a brighter tomorrow where humanity abandons carbon fuels and switches to solar panels.

The film is less knowingly postmodern in its use of imagery, with its motorbikes from Akira and masks from V for Vendetta. I was tempted to bring up games again as a comparison – parasitically feeding off ideas generated in other mediums. However, conversations with still-active gamers (I only occasionally relapse into booting up Baldur's Gate) have underlined that, actually, games ARE innovative. It's just that, like everything else, there's a lot of derivative crap out there. And upon reflection, there are games I've played (Planescape: Torment, Alpha Centauri) that built worlds like nothing I had seen before.

Back to the point: Sky Blue isn't showing you anything new. The accumulation and combination of existing elements could have been made an asset, however, if it thoroughly embraced the potential such a strategy holds out for symbolic layering. Steal and repurpose, quote and re-contextualize. Abandoning the rigours of science fiction and sticking to archetypes and symbols would have been a striking effect, espesh combined with the inherently distancing computer-generated visuals. It's what Jodo's The Incal is all about.

The worst aspect of the film is the terrible characterisation, made x1000 worse by the insipid English dub (no other option on the DVD). While watching, I kept imagining alternatives not taken – Cade more heroic, Locke more human, Moe being gay for Zed. Anything to enliven the horribly predictable maneuvers each character makes. Notionally our protagonist is Jay, who is in the middle of a love triangle between Clint Eastwood-voiced rebel-rebel Shua and soft-spoken backstabbing turtleneck Cade. Her lack of personality is alarming. The only other female character is a scared little blind girl groping for someone with agency to care for her, a fitting summation of the way Jay is treated by the film. Being stuck behind those eyes is asphyxiating. A more interesting character (this is overstating it slightly) is Cade. There is a nice circularity to his conversion: he separated Jay and Shua and abandoned the latter to his death, now he unites and saves them both. Perhaps he would have been a better narrator.

The film is less knowingly postmodern in its use of imagery, with its motorbikes from Akira and masks from V for Vendetta. I was tempted to bring up games again as a comparison – parasitically feeding off ideas generated in other mediums. However, conversations with still-active gamers (I only occasionally relapse into booting up Baldur's Gate) have underlined that, actually, games ARE innovative. It's just that, like everything else, there's a lot of derivative crap out there. And upon reflection, there are games I've played (Planescape: Torment, Alpha Centauri) that built worlds like nothing I had seen before.

Back to the point: Sky Blue isn't showing you anything new. The accumulation and combination of existing elements could have been made an asset, however, if it thoroughly embraced the potential such a strategy holds out for symbolic layering. Steal and repurpose, quote and re-contextualize. Abandoning the rigours of science fiction and sticking to archetypes and symbols would have been a striking effect, espesh combined with the inherently distancing computer-generated visuals. It's what Jodo's The Incal is all about.

The worst aspect of the film is the terrible characterisation, made x1000 worse by the insipid English dub (no other option on the DVD). While watching, I kept imagining alternatives not taken – Cade more heroic, Locke more human, Moe being gay for Zed. Anything to enliven the horribly predictable maneuvers each character makes. Notionally our protagonist is Jay, who is in the middle of a love triangle between Clint Eastwood-voiced rebel-rebel Shua and soft-spoken backstabbing turtleneck Cade. Her lack of personality is alarming. The only other female character is a scared little blind girl groping for someone with agency to care for her, a fitting summation of the way Jay is treated by the film. Being stuck behind those eyes is asphyxiating. A more interesting character (this is overstating it slightly) is Cade. There is a nice circularity to his conversion: he separated Jay and Shua and abandoned the latter to his death, now he unites and saves them both. Perhaps he would have been a better narrator.

23.6.12

Porco Rosso

Better than Kiki, not as good as Laputa... (I've seen so many Miyazaki films now I'm getting the urge to rank them) This one is also built around Miyasaki's enthusiasm for flight. And also, maybe, Casablanca? With the jazz bar full of criminals and the protagonist full of inner demons. An enigmatic, cursed, noble but fallen hero, an anarchist giving his life to fight off fascists. A Byron, except of course it's not Byron, "It's mine! See you later!"

The most striking scene in the film is the bedtime story in which Porco describes his near death experience and transformation. Reversed when, as with the frog prince, he is kissed by a woman who loves him. The link between the two events is Gina, it seems. Her first husband was Porco's comrade, now dead. Perhaps Porco's swinish form is a symbol for survivor's guilt, which fades when he receives an unequivocal sign that Gina has moved on. There is a certain logic to that interpretation, tho it feels a bit pat, and I'm pretty sure Miyazaki had deeper things on his mind.

My guess would be that it's a gender thing again. Boys will be boys going off to fight stupid wars, marrying sweethearts and getting themselves killed. Porco survives all that disfigured, convinced of the end of innocence, the darkness of man's heart. And the women, Fio, Gina, are there to redeem the world. By showing that they are just as resourceful as men, and kinder too.

The most striking scene in the film is the bedtime story in which Porco describes his near death experience and transformation. Reversed when, as with the frog prince, he is kissed by a woman who loves him. The link between the two events is Gina, it seems. Her first husband was Porco's comrade, now dead. Perhaps Porco's swinish form is a symbol for survivor's guilt, which fades when he receives an unequivocal sign that Gina has moved on. There is a certain logic to that interpretation, tho it feels a bit pat, and I'm pretty sure Miyazaki had deeper things on his mind.

My guess would be that it's a gender thing again. Boys will be boys going off to fight stupid wars, marrying sweethearts and getting themselves killed. Porco survives all that disfigured, convinced of the end of innocence, the darkness of man's heart. And the women, Fio, Gina, are there to redeem the world. By showing that they are just as resourceful as men, and kinder too.

18.5.12

Origin: Spirits of the Past