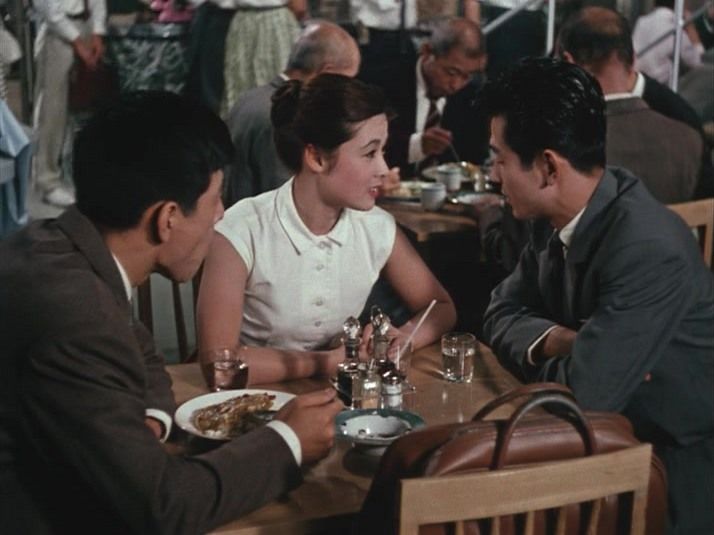

Masumura made a lot of films, only the more unconventional of which are well known in the West. I saw this at the BFI, and doubt it has a DVD release. There is no hint here of the perversities of Blind Beast or the gore of Red Angel. That said, Masumura’s interest in awkward family dynamics is front and centre, even if the genre is melodrama, and the ending happy.

Or so it may seem. Yuko is a Cinderella who finds a Prince Charming, but given everything we see of Tokyo living you wonder whether she was better off staying true to her roots and choosing the local boy from her village (her teacher, but that’s ok apparently). Yuko is illegitimate, and her father did her a favour when he sent her away from his nightmare of a family. Masumura is very good at showing that the fault ultimately lies with him. He was never reconciled to the loveless marriage he was talked into, and his indifference turned his wife into a harpy and his children into brats.

Yuko marries for love, but it’s another posh boy. There’s a subtle class divide bisecting the characters in the film, which Yuko steps over. A philosophy grad, Masumura’s sympathies lie closer to the philosophy-spouting delivery boy, as well as the hard-pressed family maid and the striving teacher-come-artist.

The plot comes from a novel, and Masumura handles the twists deftly. There’s a good deal of fancy camerawork where wide shots move into to closeups and back. And a satisfying shape to the film is provided by the opening and closing scenes on the shore, where blue sky thinking is embraced as a survival mechanism and then discarded when no longer needed. It’s accomplished, in other words, and goes to show that Masumura was good at this sort of thing. There’s a reason he made so many movies.

Showing posts with label Yasuo Masumura. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Yasuo Masumura. Show all posts

18.11.17

3.11.17

Red Angel

A very grim war film focused on a nurse on the front line and with plenty of horrible amputations, vomit and blood. As usual with Masumura, things take a turn for the bizarre and depraved. The hero is an angel in hell, who cannot countenance being responsible for other people’s deaths. The first of her ‘victims’ raped her, but she still tries to save him, in so doing establishing her saintly nature.

The film is at its most interesting when it explores the strange power dynamic of being a woman surrounded by damaged men. Nishi must suffer frequent sexual assault, but she is also the one holding soldiers down when their limbs are being removed. She is in a position to torture her torturers, but she never takes the opportunity, being loyal to the last.

Instead the film establishes a melodramatic romance between Nishi and a taciturn surgeon who is addicted to morphine. The drug makes him impotent, and Nishi has to hold him down as well through his withdrawal to cure him from that ailment. She helps to make a man out of him, and he dies with a broken sword in his hand. But she also gains power. In the sweetest scene in the film, the surgeon allows her to put on his lieutenant uniform, serves her wine and treats her like a man. Granted, he refuses to give her his sword and gun (there are limits to cross dressing and female empowerment), but it’s still a striking moment of reciprocity and empowerment.

The film is at its most interesting when it explores the strange power dynamic of being a woman surrounded by damaged men. Nishi must suffer frequent sexual assault, but she is also the one holding soldiers down when their limbs are being removed. She is in a position to torture her torturers, but she never takes the opportunity, being loyal to the last.

Instead the film establishes a melodramatic romance between Nishi and a taciturn surgeon who is addicted to morphine. The drug makes him impotent, and Nishi has to hold him down as well through his withdrawal to cure him from that ailment. She helps to make a man out of him, and he dies with a broken sword in his hand. But she also gains power. In the sweetest scene in the film, the surgeon allows her to put on his lieutenant uniform, serves her wine and treats her like a man. Granted, he refuses to give her his sword and gun (there are limits to cross dressing and female empowerment), but it’s still a striking moment of reciprocity and empowerment.

11.9.16

Manji

Another adaptation of a Tanizaki novel by Yasuzo Masumura, with

concerns similar to his version of The Tattoo. Again the focus is on the ‘demon woman’, a sexually irresistible but

manipulative creature who traps and kills her lovers. In The Tattoo we see the way such monsters are created quite

explicitly – Otsuya is unwillingly transfigured by her tattooist and the

gangsters that employ him. In Manji

the infection is not consciously administered by representatives of the

patriarchy. Rather it is imbibed unwittingly as a result of treating women like divine beings.

Like in The Tattoo,

the femme fatale in Manji is shown

a picture which provides the model for her later behaviour. It’s not a vampire

standing on a pile of corpses, but the Goddess of Mercy – an extremely popular

deity in Japan who guides the souls of the deceased to their final resting

place. The picture is drawn by Sonoko in an art class she attends to get away

from her boring husband. There she meets and is smitten by Mitsuko, who begins

an affair partly to cause a scandal and escape her boyfriend.

Tanizaki’s protagonists are usually ‘women-worshippers’, and

here he transfers that tendency onto a female protagonist. He was writing in

the 1930s, and his motives may not have been entirely enlightened – the ‘unnaturalness’

of the lesbian love affair might be a way to highlight how ‘unnatural’ Mitsuko’s

allure is. In any case, the urge to put people on pedestals becomes dangerous –

Mitsuko becomes both infantilised and insatiable as a result of having disciples. The

attention of one person isn’t enough. She wants many lovers, all jealous of

each other.

Mitsuko ends up living up to her identification with the

Goddess of Mercy. She ensnares Sonoko’s husband and instigates a ménage à trois in which she is the

dominant partner, receiving all devotion. The final part of the film becomes

increasingly weird – Mitsuko behaving like a cult leader with complete sway

over the couple who love her. When their unconventional arrangement is revealed

in the press, she argues for suicide, and in a very strange ritual the three light

incense in front of her picture as the Goddess of Mercy, before drinking

poison.

But Mitsuko cannot help toying with her worshippers, even

after death. She spares Sonoko, who is now filled with doubt about whether

Mitsuko truly loved her, or whether she preferred to spend the afterlife only

with her husband. Her faith is tested – she's left agonising about whether the Goddess she devoted herself to was just a figment of her imagination.

Masumura’s title is the Japanese name for the swastika – the

four bent arms of the cross symbolising the four crooked relationships in the film.

But it also highlights the theme of bringing the sacred into profane matters. It's a warning that attaching

a spiritual dimension to the workings of love and lust is a recipe for death or despair.

31.10.15

Tattoo (Irezumi)

A rather melodramatic adaptation of the Junchiro Tanizaki novella by Yasuo Masumura, who adds plenty of ostentatious fights and writhing deaths. But as with Blind Beast, Masumura is adept at chronicling the subtle shifts in his characters' descent into nihilism and depravity. Otsuya starts of as a willful young girl eloping with her father's apprentice Shinsuke. She cares for him, and he is besotted with her, but their relationship is pushed past breaking point as they get swallowed up by the underworld. Shinsuke becomes a killer, and Otsuya a whore, largely by circumstance, but the more courageous Otsuya is better able to capitalise on her predicament. She starts to use the enthralled Shinsuke to enact her revenge on those who betrayed and exploited her, but she gradually loses interest in him as the body count rises and the prospect of becoming a concubine to a well-connected samurai opens up.

This descent is encapsulated by the tattoo Otsuya is forcibly given at the behest of her pimp Tokubei, a jorō spider with a woman's head that feeds on blood. As part of her initiation, Tokubei shows Otsuya a painting of a geisha standing on top of a pile of corpses – a visual imprinting of the role she will assume. The tattoo is a symbol of her monstrosity, yes, but it is one forced on her by the men who kidnap and prostitute her. The tattoo artist speaks about the way his soul has escaped and been grafted onto Otsuya, so that her murders feel like his. To some degree they are, in that Otsuya is a product of her environment, and that environment is made by criminal men. Perhaps the artist speaks for the director of the film as well, and the writers who conceived and adapted the story. Otsuya is their creation as well, and they are by turns attracted to and then horrified by her, to the point where they deprive her of her life. But they are guilty as well – after killing Otsuya, the tattoo artist plunges the knife into his own chest.

This descent is encapsulated by the tattoo Otsuya is forcibly given at the behest of her pimp Tokubei, a jorō spider with a woman's head that feeds on blood. As part of her initiation, Tokubei shows Otsuya a painting of a geisha standing on top of a pile of corpses – a visual imprinting of the role she will assume. The tattoo is a symbol of her monstrosity, yes, but it is one forced on her by the men who kidnap and prostitute her. The tattoo artist speaks about the way his soul has escaped and been grafted onto Otsuya, so that her murders feel like his. To some degree they are, in that Otsuya is a product of her environment, and that environment is made by criminal men. Perhaps the artist speaks for the director of the film as well, and the writers who conceived and adapted the story. Otsuya is their creation as well, and they are by turns attracted to and then horrified by her, to the point where they deprive her of her life. But they are guilty as well – after killing Otsuya, the tattoo artist plunges the knife into his own chest.

6.8.15

Blind Beast

There's quite a lot to unpack in this erotic horror retelling of Beauty and the Beast, made by Japanese New Wave director Yasuo Masumura. It's partly a compact and meaty drama with three characters in a couple of sets slowly pulling each other apart. The central dynamic is the sheltered child-man detaching himself from a devoted but overbearing mother and being seduced by a new woman of the 1960s keen to push the boundaries of art and sex. The gradually escalating scenarios of ploy and counter-ploy between the mother and the new arrival contain some impressive character work. Like with the Oshima films I watched previously, there is a nod to the idea of a more individualistic generation breaking the bonds of duty that tie them to parents, family and society more widely (which may reflect a debt to Ozu as much as a prevalent mood in the culture of the time). A town/country divide is also alluded to – the artist's model is a city girl, whereas her kidnapper is a naive country bumpkin who is unprepared for the duplicity of his captive.

The film takes a sudden gear shift away from this tight three-way drama as soon as it is (violently) resolved. The almost theatrical family struggle is bracketed by a more cinematic exploration of images as a mechanism for dampening the awesome power of physical sensation. There is some confusion here, because Masumura's portrayal of blindness in part evokes the desire of the audience to feel their way through an image and into the fantasy it portrays. But it also represents the danger of living a life without images. The sense of touch becomes obsessive, and without the distancing effect provided by seeing things, ultimately brings humanity down to the level of insects and jellyfish. The photos Aki poses for have her bound up in chains. In Michio's warehouse, where hundreds of gloopy sculptures of body parts cover the walls, those chains are removed, and sculptor and model both lose themselves in a masochistic, sexual frenzy. Desire and dissolution melt together.

The sculpture Michio creates magically crumbles as its real-life subject is mutilated and destroyed. By this stage, the sense of otherwordly fairy-tale has completely enveloped the film, and it doesn't come as a surprise. But what to make of it? Maybe Aki's spirit has become so infused with her simulacrum that she becomes a work of art in her own right – an idea rather than a person. Or perhaps it's the director passing judgement on the two mad lovers, ensuring that no work of art escapes to stand the test of time and inspire other sybarites to emulation. There are many ways to read it, which is another way of saying that this is a film that would reward repeat viewings.

The film takes a sudden gear shift away from this tight three-way drama as soon as it is (violently) resolved. The almost theatrical family struggle is bracketed by a more cinematic exploration of images as a mechanism for dampening the awesome power of physical sensation. There is some confusion here, because Masumura's portrayal of blindness in part evokes the desire of the audience to feel their way through an image and into the fantasy it portrays. But it also represents the danger of living a life without images. The sense of touch becomes obsessive, and without the distancing effect provided by seeing things, ultimately brings humanity down to the level of insects and jellyfish. The photos Aki poses for have her bound up in chains. In Michio's warehouse, where hundreds of gloopy sculptures of body parts cover the walls, those chains are removed, and sculptor and model both lose themselves in a masochistic, sexual frenzy. Desire and dissolution melt together.

The sculpture Michio creates magically crumbles as its real-life subject is mutilated and destroyed. By this stage, the sense of otherwordly fairy-tale has completely enveloped the film, and it doesn't come as a surprise. But what to make of it? Maybe Aki's spirit has become so infused with her simulacrum that she becomes a work of art in her own right – an idea rather than a person. Or perhaps it's the director passing judgement on the two mad lovers, ensuring that no work of art escapes to stand the test of time and inspire other sybarites to emulation. There are many ways to read it, which is another way of saying that this is a film that would reward repeat viewings.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)