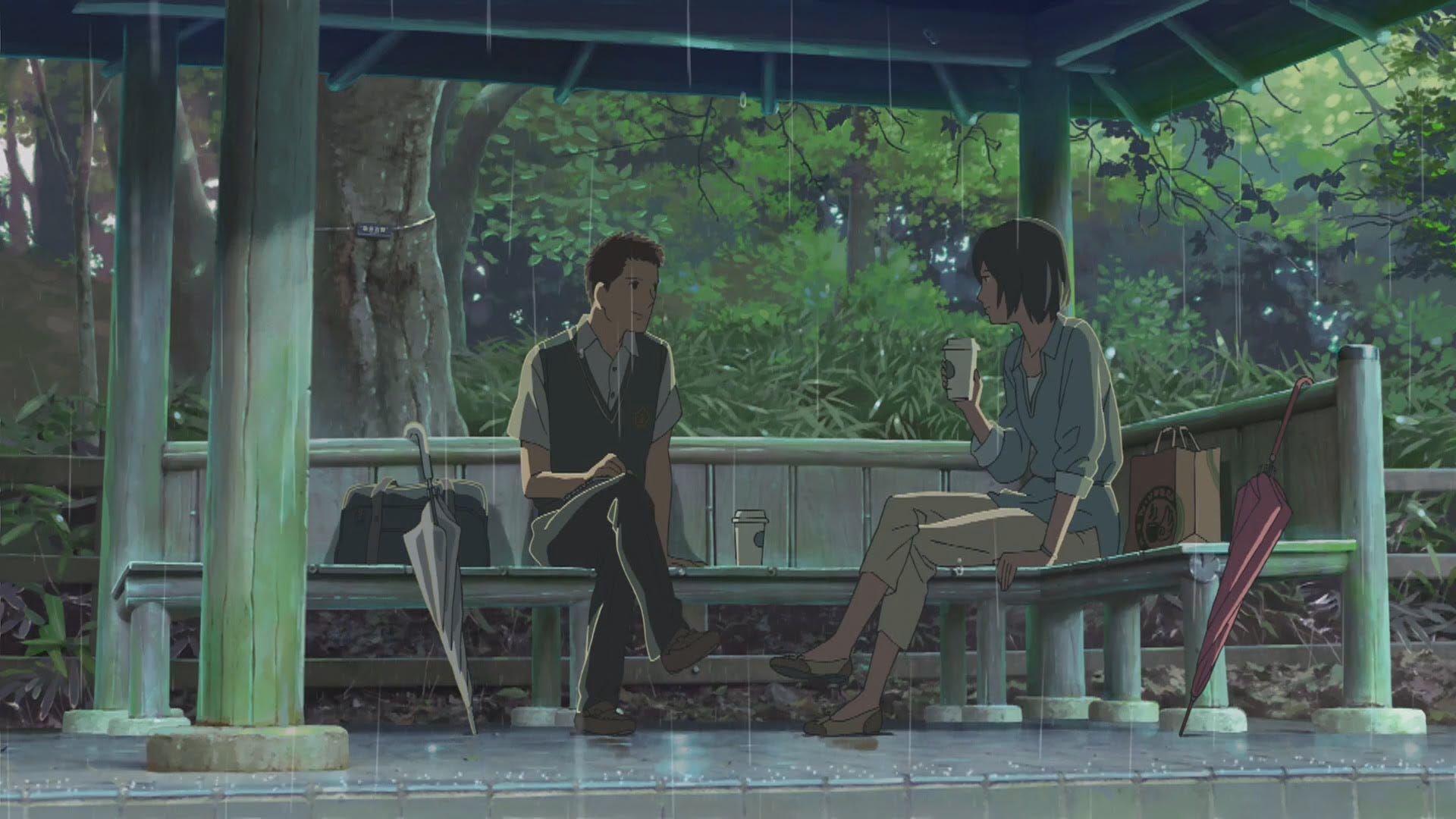

The feature Makoto Shikai made before the phenomenally successful Your Name has come on Netflix. It’s 45 mins long, and the irony of a precocious teenager teaching some life lessons to an older woman is evident even before the big reveal halfway through: that the woman is in fact a teacher at the boy’s school. A second irony is added when the teacher is hounded out of her job by false allegations of seducing a student. The repercussions of that accusation is what puts her in danger of seducing a student for real.

These ironies don’t lead anywhere, and perhaps they don’t have to. Watching this after Your Name, it’s evident that Shinkai has an interest in star-crossed lovers brought together and torn apart by fate, a force given an almost physical presence by the photorealistic hyperreal animation. It’s manipulative – a reliance on these tricks is why I dislike Wong Kai-Wai so much. For some reason, Shinaki’s equivalent is more tolerable, perhaps because we get under the skin of his characters to a greater extent than the detached cool of Wong’s lost urbanites.

Like Your Name, The Garden of Words ends on two characters on a set of stairs finally recognising each other. It’s a climax that Wong refuses to grant his viewers, and his films end up feeling emptier as a result. This, on the other hand, is generous, well-paced, and satisfying, despite the open-ended finale.

28.2.18

16.2.18

Samurai Champloo

If this makes any sense at all, it's as metaphor. One sword-wielding badass represents order and the other chaos, with the girl in the middle providing the semblance of a quest narrative. Jin follows the rules of the samurai genre while Mugen breaks them. Jin comes straight out of the Edo period and Mugen is a break-dancing hip-hop rebel. Jin is the samurai and Mugen the champloo. They are eternal and immutable opposing forces destined to orbit the female protagonist as she pursues her goal. And instead of resolution the series offers equilibrium. Backstory or progression rarely intrude on each bottle episode's brawls and scrapes.

So far so good, but the three-part finale has to lead somewhere. Fuu is the girl who yokes Jin and Mugen together to look for what turns out to be her father, who abandoned her and her mother when Fuu was a child. The idea of a patriarch who has deserted his responsibilities hangs over our angsty trio – kids without a sense of purpose or direction. The absent father may stand in for a defeated nation, destabalised gender roles, a precarious economy... you name it. Fuu is chasing the good-for-nothing bastard in order to slug him one for his dereliction of duty.

Except that in the end her father was trying to protect her all along. He did behave honourably. He did love his child. Her rage was misplaced. It's interesting that Fuu's ability to strike out on what turns out to be an extremely dangerous journey is powered by that sense of injustice, but the anime keeps stuffing this independent spirit back in the box. Because it turns out that Fuu needs Jin and Mugen, her incompetent bodyguards, to protect her on the way to her confrontation with her father. She simply cannot get by without them. The anime teases the concept of an independent woman only to put her in need of saving again and again. And in doing so, the patriarchy is redeemed.

The ending is therefore reassuring, conservative, and happy. At least there aren't any marriages. There are hints of a romantic triangle, but the anime ends by stressing the friendship between the three heroes. Their quest complete, their bonds affirmed, their demons purged, they go their separate ways. Such elemental forces are destined to wander rather than settle down. The anime is at root a chronicle of their journey together. It's only fitting that it should end when that particular journey is over.

So far so good, but the three-part finale has to lead somewhere. Fuu is the girl who yokes Jin and Mugen together to look for what turns out to be her father, who abandoned her and her mother when Fuu was a child. The idea of a patriarch who has deserted his responsibilities hangs over our angsty trio – kids without a sense of purpose or direction. The absent father may stand in for a defeated nation, destabalised gender roles, a precarious economy... you name it. Fuu is chasing the good-for-nothing bastard in order to slug him one for his dereliction of duty.

Except that in the end her father was trying to protect her all along. He did behave honourably. He did love his child. Her rage was misplaced. It's interesting that Fuu's ability to strike out on what turns out to be an extremely dangerous journey is powered by that sense of injustice, but the anime keeps stuffing this independent spirit back in the box. Because it turns out that Fuu needs Jin and Mugen, her incompetent bodyguards, to protect her on the way to her confrontation with her father. She simply cannot get by without them. The anime teases the concept of an independent woman only to put her in need of saving again and again. And in doing so, the patriarchy is redeemed.

The ending is therefore reassuring, conservative, and happy. At least there aren't any marriages. There are hints of a romantic triangle, but the anime ends by stressing the friendship between the three heroes. Their quest complete, their bonds affirmed, their demons purged, they go their separate ways. Such elemental forces are destined to wander rather than settle down. The anime is at root a chronicle of their journey together. It's only fitting that it should end when that particular journey is over.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)