This year I stopped using my streaming subscription to excavate previously inaccessible music and focused on finding new things – hence a longer list than 2017's meagre 19 entries. Most of this has been active – reading about artists and listening to their albums as complete packages. And that takes a certain amount of work, a bit more than just switching on the radio or hitting shuffle on a playlist and waiting for something to pop out at you from the ambience. This year I was willing to expend the effort, but I'm not sure that will last into 2019. I suspect I will succumb to the tyranny of the playlist, as I have to most other things.

Strange that after the glut of R&B last year there is absolutely none on the list this year. Strange also that after dismissing most rock music last year as decomposing offal there should be so much of it on the list this year – female-fronted as well, although unfortunately the boys still managed to snag the number one spot. The winds of change are blowing, and appear to be blowing in shouty ladies with guitars.

As per the established practice, it's Kieron Gillen rules. One entry per artist, with the rest of the year's body of work pushing entries up accordingly. Only four entries out of the 25 below don't have a long player behind them, so even more so than last year this is an albums list in all but name.

As per the established practice, it's Kieron Gillen rules. One entry per artist, with the rest of the year's body of work pushing entries up accordingly. Only four entries out of the 25 below don't have a long player behind them, so even more so than last year this is an albums list in all but name.

25. East Man feat. Saint P - Can't Tell Me Bout Nothing

This just in as I only just discovered it (hats off to the magnificent Quietus list for alerting me to its existence and many other things besides). Can't believe I didn't clock this album earlier, given it's right up my alley – skeletal grime riddims being jumped on by hungry young MCs, some of who sound like they are still in school. It's a call back to the era of grime before grime had a name, and as such risks being a nostalgia trip but for the fact that the voices and flows sound so refreshingly contemporary.

24. Camp Cope - The Opener

Also a new discovery. I'm still unravelling the album but WHAT a way to open it – Georgia Maq spitting quotable upon quotable as she works herself into a lather of rage at all the patronising men in her life. Her sarcastic tirade at crummy boyfriends and pious scene gatekeepers is one hell of a ride, but one shouldn't forget the chewy riff that structures the song and provides a platform for the increasingly incensed vocal performance. Provides a thrill like only the best rock 'n' roll can.

23. Charly Bliss - Heaven

OK so this is more of a placeholder for the 2017 album Guppy, which I only got round to at the beginning of this year. 'Heaven' takes its cue from Guppy's final and worst track 'Julia', which slows down the band's energy to something approaching the heaviness of grunge. It's pretty bland, in other words, and doesn't come anywhere near the sugar rush peaks of 'Percolator', 'Black Hole' and the sublime 'Glitter', the harmonies on which are truly heavenly. I'm hoping whatever comes next from the band can recapture some of those highs.

22. Space Afrika - Gwabh

One of the more propulsive tracks on Space Afrika's Somewhere Decent To Live, which is otherwise an object lesson in minimalism, stripping percussion back to almost nothing and focusing on waves and waves of deep enveloping bass. I find most dub techno pretty dry, but there's an air of mystery and depth to this album that kept it on rotation this year. I like 'Gwabh' the most because there's just the merest hint of a two-step swing to the drums – pushing Space Afrika slightly closer to the dancefloor.

21. Daphne & Celeste (prod. Max Tundra) - 16 Stars

By various curious twists of fate I found myself selling copies of this CD at a gig at which Max Tundra (the producer) was DJing. The man is an absolute gent, and I say that not just because he bought me a drink for my efforts at salesmanship. Daphne & Celeste are of course the bratty children behind the reprehensible but also brilliant anthems 'Ooh Stick You!' and 'U.G.L.Y.', which I was the ideal target audience for when they came out 18 years ago. Max Tundra's production on their comeback album retains some of the abrasive hooky excess of the original D&C brand, but the pop here is knottier, less predictable. '16 Stars' sands down some of the jagged edges, which is why it appeals me (I'm older now, I need more stability in my life). But the whole thing is a treat.

20. Appleblim - I Think We'll Let The Gas Sort This One Out

Life in a Laser feels like it's making a case that the logical endpoint of the music that evolved into dubstep isn't the Caspa & Rusko avenue of grotesque wobbles and laddy boisterousness. Appleblim comes from the opposite, cerebral, Bristol-based end of the sound, but here he mucks in and aims for the club main room, mixing genres from across rave's history with an emphasis on light and colour rather than darkness and braggadocio. 'Itwltgstoo' draws on two-step garage (always and forever an irresistible rhythmic pull for me) but it's refined by the micro-editing precision of techno. A banger for the connoisseurs.

19. OneMind - Vibrations

The first of two future classic drum and bass albums released this year by the legendary Metalheadz label. OneMind sticks pretty close to the template established by Goldie and Platinum Breakz all those years ago – even the cover art is a tribute to the look and feel of those late 90s releases. Many of the best tracks are culled from the impressive EPs released last year, 'Pull Up' being a personal favourite. 'Vibrations' could have been a pretty straight two-step roller except that almost every bar is tuned and twisted in intricate ways that draws your attention inwards. OneMind take attention to detail – a prerequisite for practitioners of the genre – to new depths of obsessive compulsiveness. It's a pleasure to hear the effort in their work.

18. Wiley (prod. Bless Beats) - Remember Me

Godfather 2 may not be as consistent or as grimey an album as last year's back-to-yer-roots Godfather, but it's more honest, as well as having better pop moments. 'Remember Me' is particularly precious as an entry in a long line of Wiley self-doubting confessionals – valuable especially given the contrast with how he flipped out at Skepta recording a tune with prodigy-turned-nemesis Dizzie Rascal this year. "I used to be an eediat running my mouth in the beef with the paigons" – except that it turns out Wiley hasn't learned, he's still at it, still can't let go. The man's legacy is monumental, but even the recognition that comes with an MBE is not enough to settle old scores. 'Remember Me' is an all-too-brief moment of stepping back and giving thanks, before the insecurities and competitiveness drive him back into the war.

17. WSTRN - Sharna

God bless and preserve BBC Radio 1Xtra for bringing to my attention tunes that would otherwise never come within my hoary earshot. This little delight filled a similar niche to last year's much-loved balmy dancehall groover 'Reverse' by Shenseea (no 2 on the 2017 list). Only recently found out that Sharna is actually an acronym for 'She has a really nice arse', although the way these boys talk it sounds like they mostly want to snuggle up with the object of their ardour and drift blissfully to sleep.

16. Blocks & Escher - Gulls

The second of two future classic drum and bass albums released this year by the legendary Metalheadz label. The cover of Something Blue evokes the sea, as do several track titles, and there is something rather serene and balmy about parts of the record. I ended up listening to it quite a lot when I was by the beach on holiday. The drums don't really kick in until halfway through 'Gulls' – most of it is just atmosphere and a sound effect halfway between gull squawks and sirens. But there's nonetheless a hint of danger underneath the tranquil surface. That tension means you never quite sink into complacent easy-listening – there's always something around the corner to jar you awake.

15. Pistol Annies - Best Years of My Life

Pistol Annies are here to disabuse you of the notion that country music is all yee-haw good cheer. This devastator kicks off with "I picked a good day for a recreational Percocet" and it just gets worse from there. If Future (of whom more below) is the new millennium's version of the broken philandering (also pill-poppin') bluesman, Pistol Annies recount the other side of the coin – the articulate women that struggle with their own sense of Southern Gothic despair, and the men in their lives that fail to support them through it. The ironies and hard facts in the song are laid on so mercilessly it's difficult not to feel a shiver down the spine – the catalogue of disappointments building to a universal sense of the shit women put up with because they don't feel able to escape the circumstances they are boxed into.

14. Kojo Funds feat. Bugzy Malone (prod. Remedee & Mike Brainchild) - Who Am I?

Yomi Adegoke's excellent survey of current black British pop over the summer identified how grime (notionally having broken through after 15 lost years following Boy in da Corner's Mercury win) is now being squeezed by drill on one side and a medley of sounds loosely grouped as 'afro bashment' on the other. I find even the most energetic examples of drill like 'Homerton B' rather monotonous and boring, and it has made 1Xtra a less enjoyable listen given how much of the playlist is bogged down with this fodder – from the US as well as the UK. As grime dons like D Double E explain, part of the problem is the relentlessly dark and violent vibe of the genre, whereas grime always blunted that dangerous edge with humour, absurdity and lyrical ingenuity. When grime MCs 'battled' and 'slew' each other, this was mostly a metaphor for the competition pon the mic rather than in the street.

Suffice it to say that the music under the umbrella of afro bashment (the term a clumsy splice of afrobeats and 'bashment' or dancehall) appeals far more – not least because it rolls in the influence of female-friendly genres like funky and garage. 'Who Am I?' is a straight-up garage tune – calling back to the flossy excess of So Solid Crew but with the cadences updated for 2018. It's also partly a refutation of Adegoke's dichotomy, given that lyrically Kojo Funds and Bugzy Malone's concerns overlap with those of drill rappers. It's just that the beats they are jumping on are soooo much more enjoyable.

13. D Double E (prod. Swindle) - Back Then

The default position of grime MCs is to claim that they are the best grime MC, but catch them in a reflective mood and they'll concede that actually, D Double E deserves the number one spot (and also it'll be great if they could do a collab one day). For a while though I did think that D Double's best days were behind him – a lot of the singles relying on straightforward radio-friendly bars and callbacks to his classic catchphrases. A few short raps and then a chorus doesn't quite compete with the epic, dextrous torrents of verbiage he can unleash when he has a mind to (the twin pinnacles of his oeuvre remain his Frontline and Wooo Riddim freestyles). So it was a surprise to me that he largely pulled it out of the bag on his first album – released 20 plus years into a successful MC career built on radio sets, mixtapes, singles and live performances. 'Back Then' is my favourite cut because it's a sly nod to D Double's age and veteran status, because it has some of his best quips, and because there's no chorus to distract from what he does best – which is lay on bar after inventive bar.

12. Kero Kero Bonito - Visiting Hours

I used to consider these guys a singles band. Two of their best songs – 'Flamingo' and Build It Up' – were left off the concurrent long-players, and those long-players had their peaks and troughs. But this year's Time 'n' Place was a level-up, and best consumed as a whole. Although occasionally discordant and noisy, there is a persistent dream-pop vibe to the record. 'Visiting Hours' is a case in point – an almost word-for-word account of band-member Gus seeing his dad in the hospital after an accident. As sung by Sarah it becomes a paean to familial solidarity and assurance heard through the warping haze of painkillers. Delightfully comforting.

11. Natalie Evans - Hard to Forget

Was introduced to Natalie Evans when she supported Gulfer (of whom more below) at their gig in London. For a shouty mathy noisy punk band the choice of a singer-songwriter armed with a harp to open would be surprising, but then Evans's spidery songwriting does owe something to math/emo progenitors American Football – a common ancestor for both acts. So it made more sense than it seemed. Her record Better at Night is marvellously soothing, and 'Hard to Forget''s instantly memorable riff is particularly ear-wormy. Spent a lot of time with it this year.

10. Future (prod. Zaytoven) - Racks Blue

The first Beast Mode was my favourite release of Future's epic 2015 run, and its sequel is if anything even better. The third track 'Racks Blue' is where it really kicks into gear, using a pretty piano line to introduce a more melancholy, heart-tugging vibe to Future's stunting. And we shouldn't forget that he's still stunting. The topics Future covers do not stray far from trad trap bragging. The intrigue comes from the downbeat music and the grain of the voice in which they are delivered, which add the twist of decadent dissatisfaction and ennui amidst plenty. Beast Mode 2's finale 'Hate the Real Me' finally crosses the border into overt self-loathing, where you see the mask finally slip. 'Racks Blue' is the sound of Future still struggling to keep the mask on.

9. MoStack (prod. Ill Blu) - What I Wanna

MoStack's partnership with Ill Blu continues to deliver. A bit like MIST's alliance with Steel Banglez, the duo churn out variations on the same fool-proof template. This isn't much different to 2017 favourite 'Let It Ring', which I discovered quite late into the year, whereas I was cognisant of 'What I Wanna' in good time for it to be my 2018 summer banger. MoStack is a amiably awful human being – sing-rapping about being reckless and irresponsible and loving life to the max (the tune is marred slightly by a thoughtless endorsement of drink driving imho). The scamp even claims to be savvy enough to "sell a Biggie Smalls album to 2Pac", and even as a humourless old codger I find it difficult to resist this sort of brazen chutzpah.

8. Now, Now - AZ

Much as I love and admire Robyn, I'm afraid I didn't quite latch on to Honey. But that's OK though, because I had Now, Now's Saved instead. Frontwoman Cacie Dalage's vocal has that same yearning quality, and although not dance music, the loping rock rhythms of the record have a certain hypnotic effect nonetheless. The best singles came out in 2017 ('SGL' is just mahoossive), but this cut rather nicely balances the undergirding of guitar, bass, drums with a very 80s synth riff. It's about summertime and going back home and being young enough for a crush to feel like a religious experience. In fact Saved sounds a bit like CHVRCHES if you transpose them to the middle of Nowhere, USA and fed them nothing but John Hughes movies and Catholicism as they were growing up. And I'm there for that.

7. Ariana Grande (prod. Ilya & Max Martin) - No Tears Left to Cry

Let's be real here: Sweetener is actually quite an uneven record. 'The Light is Coming' is a brave experiment that doesn't work, 'God is a Woman' is Sia-level bland balladry, the final two tracks are forgettable. Pharrell's best cut is the rather sedate 'R.E.M' – the rest of his contributions are pretty mediocre (OK maybe 'Blazing' is OK). Grande's masterpiece remains her debut album – the one that cleaves closest to her Whitney, Mariah, Aguilera influences. And Sweetener picks up when she comes back to the Max Martin hit factory that produced the highest highs on Dangerous Woman. Of which, 'No Tears Left to Cry' is the standout and forms the centrepiece of the album. A euphoric crunchy belter that rises like a phoenix from the pits of the despairing croonery at the beginning, and ends on the confident flounce of pristine R&B. It's a journey, in other words, and far more assured than the confused sentiment of consensus pick 'Thank U, Next'.

6. Yizzy feat. Gemin1 (prod. D.O.K.) - Like Yours

The idea behind Yizzy's S.O.S. EP was to compile a batch of songs produced entirely by the old guard of grime beat-makers, and thus craft an appeal to 'save our sound' from what I presume to be the omnipresent monotony of drill on the one hand and vapid pop on the other. Hence cuts by heavyweight originators Terror Danjah, Prince Rapid, Maniac and Treble Clef. Apart from the too-earnest manifesto of the title track, the project is a roaring success, not least due to Yizzy's full-bore flow, honed by an experience of and appreciation for pirate radio. 'Like Yours' comes closest to capturing the energy and exuberance of a radio set, with two MCs knowing, loving and trading each other’s bars as they pass the mic back and forth.

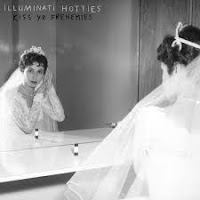

5. illuminati hotties - Shape of My Hands

A great band name, and more importantly a great band. Ringleader and songwriter Sarah Tudzin is a studio rat and the album Kiss Yr Frenemies bears the hallmarks of her production nous – the hooks sharpened the better to tug your ears with. A bit like Charly Bliss above, illuminati hotties' indie-rock harks back to the sorts of songs you would hear in the background of bad 90s teen comedies, except that now the girls that watched those films have picked up guitars and are writing their own hits. 'Shape of My Hands' is still stuck in teenagerdom – all about how clumsy you are at romance when you miscommunicate through songs rather than trying to speak directly to each other. "Are you still thinking about me?" goes the refrain, and I think most loved-up sixth-formers know the feeling. 'Shape of My Hands' is almost too cute for its own good, but for me the callback to simpler times was hard to resist. Also, to borrow a Tudzinism, the whole album absolutely shreds.

4. Proc Fiskal - Kontinuance

Insula is a bit like what Burial would make if he grew up in Edinburgh listening to old Wiley eskibeat tunes on YouTube. It's a patchwork of influences, made more insular (hence the name) and personal by the inclusion of random chat the producer recorded when out around town with his friends. The stitching is too dense to unravel, really. There's only so much you can understand of Proc Fiskal's personal universe, but there's something intriguing in trying to follow the threads. Proc Fiskal's focus on the record was melody rather than needing to deliver the rhythmic punch the dance-floor demands. 'Kontinuance' adds to that by utilising two bars from an unidentified MC to creates a hook for the song to weave around. The final moments revert to the hiss of a radio moving between stations, which suggests a nod to the legacy of pirate radio, and the continuum of music Proc Fiskal's work is indebted to.

3. Skee Mask - Via Sub Mids

Compro is just such an endlessly listenable techno record, which is not something I say often about techno records. Care and attention is devoted to a sturdy rhythmic underpinning, borrowing freely from the breakbeat science of jungle in its prime. But there's also a warmth and emotion that comes from the atmospheres smeared over the drums. There are harder cuts on the album, but 'Via Sub Mids' stands out for the understated way it deploys its tools. The drums here almost sound like raindrops, the hypnotic drones over them like a cloudy sky slowly moving to reveal the glimmer of an obscured sun. And the drop in the middle is all the more effective for not being telegraphed. A gorgeous piece of work. Jon Hopkins's feted but meandering Singularity can learn a thing or two from it.

2. The Ophelias - General Electric

The origin story is a good one. The band are comprised of musicians who all served as token girls in other bands playing various genres in their home town. The name is pointed and ironic – Ophelia is Hamlet's beau, rejected by the philosopher prince and ending up mad and dead when she loses father and lover. This feels like a rehabilitation exercise, part of a trend of women in indie rock asserting themselves more than ever this year. 'General Electric' brings to mind the early work of St Vincent – meticulous, controlled compositions which seethe with suppressed aggression (I still maintain that St Vincent's masterpiece is the first song of her debut album). The Ophelias sing "I want to be just like the girls you like" in the same mocking Stepford Wives-esque tone, as if they are robots slowly becoming aware of their programming. It's a song about power being ceded to a lover ("I control nothing", "control me like a puppet") because these are the unwritten rules by which relationships are supposed to run. And the song itself sounds like an explosion waiting to happen – one that never quite arrives.

1. Gulfer - We've All Done Wrong

Math rock is supposed to be angular and precise – all of that fiddly fretwork takes a certain amount of skill and patience. Gulfer are very good at it, but their songs still sound scruffy. Perhaps it's the grain of the voices (vocal duties are shared throughout, one band-member often 'double-tracking' another at select moments), all of which have a strained quality, as if they are working towards a clear-throated singalong and never quite get there. Perhaps it's the texture of the recording – which still sounds like it could have taken place in the basement referred to in the opening song on the album. Perhaps it's the lyrics, which are vague and occasionally clumsy. There is a constant tension throughout Dog Bless between order and chaos, or the will to create something perfect from imperfect materials. There are many moments when the band get close. The final song on the album strings three such moments together, and therefore comes closest. It has a pedestrian beginning, but it ascends, and climbs peak after peak. It's the sound of pulling together at the last minute, working through the tiredness until you get at a moment of peace and serenity. And the sense of achievement is magnificent.